Parole

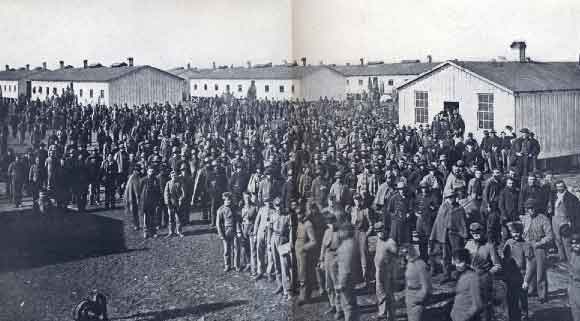

(Five unidentified prisoners of war in Confederate uniforms in front of their barracks at Camp Douglas Prison, Chicago, Illinois. Image courtesy of the Library of Congress).

We are going to have to spend a minute on the social issues that went along with the Civil War. I would rather contemplate the remarkable Triple Crown win by American Pharaoh, but I am ambivalent about the Sport of Kings and how the horses are treated. So, despite the fact that this is the first horse to win the three races since Secretariat, I will leave it at that.

I think most folks agree that there was never as transformational a period in American History as the years between 1861-65. The conflict started over the most profound issue possible, though it was clearly seen in radically different contexts.

Neither of my Irishmen had much to do with Slavery, the abomination of our history. James joined the Union because he lived in Ohio. Patrick joined the confederacy because he lived in Nashville, and Colonel McGavock, the dashing former mayor, was recruiting a Company of troops to fight for his state, not a perverse and immoral institution.

Blogger Bill Borst summed it up nicely when he cited the dialogue in the epic movie, Gettysburg, based on the late Michael Shaara’s powerful novel The Killer Angels. He wrote: “A young Union officer asked a group of prisoners why they were fighting the bloody war. The most vocal of the trio said that “we’re figthin’ for our rats!”

He probably perceived the Northern invasion of their sovereign state territory as a wildly aggressive action of the central government, rather than a struggle over the South’s distinctly limited definition of human rights.

I doubt if the irony of the situation could be fully appreciated, since no mention was made of the injustice of slavery or the fact that he was standing in Pennsylvania when he uttered his principled words. Of course the only response would have been who started what.

Obviously, views on the matter were strong enough that hundreds of thousands of young men were willing to die over it, though at the beginning it was beyond the comprehension of most participants of the scope and brutal nature of the total war to come.

Just one of the issues confronting the two governments in America- there were several dozen major ones- was the subject of what was to be done with prisoners taken on the battlefield.

An early (and continuing) solution for the North was the establishment of prison camps. There is one of them that is little known now, but resonates with me strongly: Camp Douglas, located on the South Side of Chicago. It was out in the country then, and occupied roughly four square blocks, or about eighty acres.

Originally a camp for Union enlistments and training, it was converted to a prison in February of 1862 after Sam Grant’s troops opened the River War. He captured 5,000 Confederate soldiers at Fort Donelson on the Tennessee-Kentucky border. With nowhere else for the captured troops to go, Camp Douglas became a Army prisoner-of-war camp, and it stayed one for the duration of the war.

Chicago’s role as a transportation hub made it an ideal location for a prison. It was directly off the Illinois Central Railroad. At the time, this was the longest railroad in the world, running from Cairo, Illinois, along the Ohio River, to Chicago. Once captured, Confederate prisoners were only a steamboat and train ride away from Camp Douglas.

One of them was Great Great Uncle Patrick.

I will let him tell you about it himself:

“…the “Tinth” (Tennessee ) was surrendered at Fort Donelson without their knowledge or consent, and for the first time since we left Nashville, Lieut. Col. McGavock and I were parted. He was sent to Camp Chase, and I with Company H to Camp Douglas.

Most of you are conversant with the routine of prison life. I will not go into detail regarding it Suffice it to say that I served with distinction as orderly sergeant of Company H, having been sent to the “Black Hole” oftener than any other orderly sergeant for overdrawing rations and clothes. Doubtless I would have gotten into very serious trouble during the first few months of our imprisonment were it not that Col. Mulligan, the commander of the post, was an Irishman, and, hearing that my name was Pat, he took me for an Irishman, too; and, although he was a Yankee, he had a heart. Some of our fellows were in bad shape there, and they certainly needed all that I could get for them.

All of the prisoners regretted the removal of Col. Mulligan; and well they might, for it was a “son of a gun” that came after him—Col. Tucker. It makes me mad now to think about him. We had to fortify our bunks, and did not dare to poke our heads outside of the barracks after night- fall unless we were willing to have bullets pitched our way. We were offered every inducement to take the oath or join the Yankee army. But after meeting Col. Tucker, I knew that it would be impossible for me to ever become a Yankee.

Very few of the boys went over to the other side. I think those of us who were there found the latter portion of that seven months about the worst part of our existence. It is needless to say that the news of exchange was a matter for general rejoicing; and when Col. Tucker and Chicago faded from sight we felt as if we had gotten out of the devil’s clutches.”

As many as 5,000 Confederate troops died there, and Patrick and his comrades in Company H were lucky. They were the beneficiaries of the extended negotiations that resulted in a thing called the Dix–Hill Cartel, an agreement concluded on July 22, 1862 between Union General John A. Dix and Confederate General D. H. Hill to handle the general exchange of POWs from both sides.

The agreement became necessary because of parallel pressures. At the outbreak of the conflict, Washington struck a tough attitude regarding Rebel prisoners. The Lincoln Administration wanted to avoid any action that might appear as “an official recognition of the Confederate government in Richmond, including the formal transfer of military captives.”

Understandable, of course, but the fate of the thousand Union prisoners taken at First Bull Run (Manassas) directly influenced public opinion. Prior to Dix-Hill, Union and Confederate forces only exchanged prisoners sporadically, usually as an act of humanity between opposing field commanders. In many cases, transfers were only made for sick and wounded captives. Everyone was new at this business of Civil War, and many commanders were reluctant to negotiate with the enemy without guidance from their respective Chains of Command.

The Dix-Hill agreement established a ‘scale of equivalents’ by which a Navy Captain or Army Colonel would be valued at fifteen enlisted troops, while private solider like Uncle Patrick would be exchanged at the rate one one-to-one. Two locations for the exchanges were designated, one at Aiken’s Landing near Dutch Gap, VA, and the other at Vicksburg, MS. Each government appointed agents to manage the parole of prisoners and the exchange of captives between the commanders of two opposing forces.

There is an important distinction between “Parole” and “Exchange.” In addition to provisions for the exchange of non-combatants, Dix-Hill directed authorities to parole any prisoners not exchanged within ten days following their capture. Paroled prisoners were prohibited from returning to the military in any capacity including “the performance of field, garrison, police, or guard, or constabulary duty.”

The system began to fall apart at the end of 1862, when a Louisiana politician named William Mumford was executed for the crime of ripping down a U.S flag by Union General Benjamin Butler. There were other things that were starting to change with the nature of the war, and the massive number of casualties at Shiloh was a large part of it. A battle that produced 27,000 casualties in two days shocked the citizens of both countries, though that would hardly be the bloodiest battle of the war. The Armies were getting much better at the art of slaughter.

As I said, Patrick was lucky. Exchanges were essentially done by the time that Vicksburg fell in 1863.

Patrick described his return this way:

“At Cairo, our officers were waiting for us. Most of them were looking the worse for wear, but oh how good it was to know that those of us who were faithful were together again!

From Cairo we went by boat to the island above Vicksburg, where Grant was trying to change the course of the Mississippi and from this island we were ferried over to Vicksburg. After landing, we marched to a field outside of the city, where the ladies had prepared a grand barbecue for us. It is hardly necessary for me to tell you how we boys did justice to all the good things.”

There were not many good things to come for the troops. There was a growing and systematic brutality to the conflict, and new horrors yet to come. That goes along with the Anaconda Strategy, a system of internal and external blockade by which the North was determined to starve the South into submission.

And then there were war crimes and war criminals, all of which were going to be experienced by Great Great Grandfather and the men of the 72nd Ohio Volunteer Infantry, and a place that became known as Andersonville.

More on that tomorrow.

(Union General Winfield Scott’s Anaconda Plan in the popular view. Library of Congress)

Copyright 2015 Vic Socotra

Twitter: @jayare303