Patrick Griffin Speaks

Gentle readers, the following paper was read by Patrick Griffin at a meeting of Frank Cheatham Camp, Confederate Veterans of America, at Nashville, Tennessee in the year 1905. The Wright Brothers had just flow the first successful airplane two years before. It is the overlap of generations that is striking here- Patrick had been brought to America from Ireland as an infant, fought in the Civil War as a young man, and now, as a gray-beard in a new century, told his tale to a dwindling number of comrades. In a fighter squadron it was always important to be first to the blackboard in order to establish who had “won” a mock engagement. In terms of memory, though. Patrick was the last man standing, and the only one left who knew the real details of his story. It is a characteristic reminiscence of the famous Irish regiment, and was published in the Nashville, (Tenn.) American as fact.

It is pretty amazing to hear the words of your ancestors, spoken 110 years ago, about events that had happened more than a century before. For his address, Patrick wore a Confederate Officer’s uniform of his own design, took a sip of water, cleared his throat and began to speak:

“I appreciate the opportunity to tell you something about my old regiment, the “Bloody Tinth” Tennessee Infantry, Irish, and to give you a few glimpses of a clean, strong, brave man, a noble soldier, a loyal friend, Col. Randall W. McGavock. What a multiplicity of things the sound of that name brings to mind! Across the years I hear the tread of marching armies and the notes of the fife and drum.

Once again Capt. McGavock ranges his company in Cheatham’s store on College Street. The command is given for the “Sons of Erin” to march, and I find myself walking with old Jimmy Morrissey and making an earnest effort to drown the sound of his fife in the glorious strains of “The Girl I Left Behind Me.”

Jimmy Morrissey had been a fifer in the English army, so this going to war was nothing new to him; but I was the proudest boy in the world without a doubt, for, notwithstanding the fact that my mother had repeatedly declared that I was under age and had on one occasion taken me out of the ranks and led me home by the ear, the conceit would not down that the war could not be carried on unless I were there to make the music, and so on that never-to-be-forgotten day when we marched down to the wharf and boarded the steamboat B. M. Runyon I would not have been willing to exchange places with Gen. Lee.

On the day we embarked, Capt. McGavock came up to the standard of my ideal, and I styled him “God’s own gentleman.” While it was only a boy’s thought, I never have found a more appropriate title for him. I might spend the night idling you of innumerable noble deeds that could be traceable back to him. My mother was there in the crowd on the wharf with several of my relatives, and a slip of a girl with blue-gray Irish eyes and auburn hair stood out from amongst them to wave her hand to me.

I can almost see the sunlight on the water and the two big fellows who jumped overboard Martin Gibbons and Tom Feeny. They could not stand the pressure; but they were picked up, and as the boat started up the river to make the turn Jimmy Morrissey and I started up the same old tune of “The Girl I Left Behind Me,” and we kept it going till the hills around Nashville had vanished from sight.

At Clarksville, we started in on it again, and another member of the company jumped overboard. Then the captain advised us to give them something else, so after our comrade was rescued we gave them old “Garry Owen” all the way down to Dover.

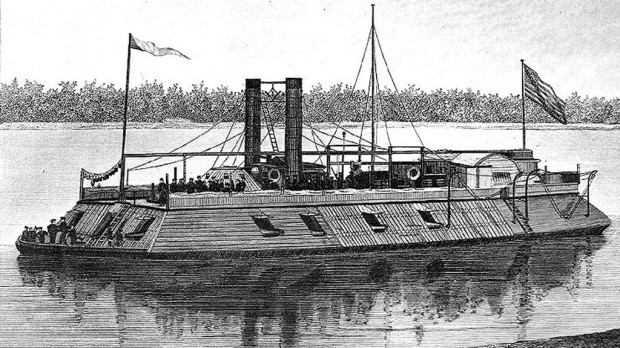

At Dover we helped to build Fort Donelson. Later, after the “Sons of Erin” became Company H, 10th Tennessee Infantry, we went down on the Tennessee River and built Fort Henry. At Fort Henry there was no whisky on our side of the river, but across the stretch of water was Madame Peggy’s saloon. There was some mystery as to where the beverage she sold was obtained, but this only added to her popularity. Many an amusing incident had its root branch in Peggy’s shop.

One of these, treasured in the memoirs of Capt. Tom Gibson’s company, I will relate: One night Paddy Sullivan and Timothy Tansey went over to Lady Peggy’s to get some whisky; and when they returned to the river bank a small cloud appeared upon the horizon. They paid no attention to this, however, but rowed out into the middle of the wide Tennessee River. A squall suddenly overtook Paddy and Timothy. The waves got so high that the brave ladies thought their time had come. Timothy said to Paddy: “Bejabbers, Paddy, and the boat will lie overturned and we will lose our whisky.”

Says Paddy to Timothy: “Be sure and we won’t; we will just drink it and save it.” And drink it they did.

The refreshment added to their courage and strength, and they reached the shore, but the boys in camp were minus their jiggers. Peggy did a land office business until Col. Heiman ordered all the skiffs and small boats in the neighborhood smashed. I never visited her shop until after the destruction of the boats. All my life I had had a close acquaintance with water, so the old river held no terrors for me, and only a short interval elapsed before I was commissioned courier and general canteen bearer between Peggy’s and the fort. The hours were brimming over with fun.

Most every night we had a stag dance, and there was an exchange of visits right and left, and no time to think of the dark days ahead. We had not been at Fort Henry very long when we got our full quota of Irish companies to make a regiment, and Capt. McGavock became-lieutenant colonel of that regiment-the 10th Tennessee Infantry, Irish. In the new companies that came in, several better drummers than I was were found, so I had to hand over my instrument; and to console me for the toss they made me orderly sergeant of the “Sons of Erin,” now Company H.

At Fort Henry we got our first taste of bombshells, and we went back to Fort Donelson to make the acquaintance of Minie balls. It was at this period that the regiment won its sobriquet of “Bloody Tinth” It happened in this way: At the evacuation of Fort Henry it was rumored that the Yankees were trying to head us off, but for some reason the “Tinth” failed to get this news.

(General U.S. Grant pressing the Rebels at Fort Donelson).

The Yankees were pressing us closely, and the two regiments in the lead threw down their guns in order to get to Fort Donelson at a double-quick, and the “Tinth,” bringing up the rear, picked up the cast-off guns, so we had about seven shots apiece when the Yanks charged us. It is a sure-enough Irishman who will have first blood in a fight With all their fighting ability, the “Tinth” was surrendered at Fort Donelson without their knowledge or consent, and for the first time since we left Nashville, Lieut. Col. McGavock and I were parted. He was sent to Camp Chase, and I with Company H to Camp Douglas.

Most of you are conversant with the routine of prison life. I will not go into detail regarding it Suffice it to say that I served with distinction as orderly sergeant of Company H, having been sent to the “Black Hole” oftener than any other orderly sergeant for overdrawing rations and clothes. Doubt- less I would have gotten into very serious trouble during the first few months of our imprisonment were it not that Col. Mulligan, the commander of the post, was an Irishman, and, hearing that my name was Pat, he took me for an Irishman, too; and, although he was a Yankee, he had a heart. Some of our fellows were in bad shape there, and they certainly needed all that I could get for them.

All of the prisoners regretted the removal of Col. Mulligan; and well they might, for it was a “son of a gun” that came after him—Col. Tucker. It makes me mad now to think about him. We had to fortify our bunks, and did not dare to poke our heads outside of the barracks after night- fall unless we were willing to have bullets pitched our way. We were offered every inducement to take the oath or join the Yankee army. But after meeting Col. Tucker, I knew that it would be impossible for me to ever become a Yankee.

Very few of the boys went over to the other side. I think those of us who were there found the latter portion of that seven months about the worst part of our existence. It is needless to say that the news of exchange was a matter for general rejoicing; and when Col.Tucker and Chicago faded from sight we felt as if we had gotten out of the devil’s clutches. At Cairo, our officers were waiting for us. Most of them were looking the worse for wear, but O how good it was to know that those of us who were faithful were together again!

From Cairo we went by boat to the island above Vicksburg, where Grant was trying to change the course of the Mississippi and from this island we were ferried over to Vicksburg. After landing, we marched to a field outside of the city, where the ladies had prepared a grand barbecue for us. It is hardly necessary for me to tell you how we boys did justice to aII the good things.

Next we went into camp at Clinton, where we were sworn in for three years, or the duration of the the war. We elected our officers and made preparations to go on the warpath once more. Lieut Col. McGavock became our colonel- Sam Thompson, lieutenant colonel, William Grace, Major, Theodore Kelsey, adjutant. We spent the ensuing few months hunting Yanks in the country around Vicksburg, until we were ordered via Holly Springs, Miss, to reinforce Price and Vandorn, who were moving on Corinth.

We did not get there in time. but we joined the retreating army near that place and went on one of the severest marches of the War. It rained in torrents’ and the mud and water were awful. On this march many of our men, fresh from prison, were stricken with sickness. Just before we reached Grenada one evening, being sick and worn out from exposure, Capt Thomas Gibson concluded that he would leave camp and go into an abandoned Negro cabin near by for shelter.

After Gibson had got a good fire going, in came Lieut. Lynch Donnahue, of the regiment, wet and sick also. After drying their clothing and shoes a bit, they went to sleep. Gibson made a pillow of his shoes and advised Donnahue to do likewise; but the Lieutenant had more confidence in mankind and left his shoes near the fire to dry. While the two officers were sound asleep, some soldiers came into the cabin and took Lieut. Donnahue’s shoes.

Imagine the cuss words when Donnahue found his shoes gone, and he sick and the rain streaming down. Gibson was a good forager, however, and he soon hailed a servant of Gen. Price’s who was passing by the cabin, and he persuaded the Negro with some cash to procure a pair of shoes for his guest.

At Grenada we received orders to go to Jackson. We boarded the cars and were sent on to Vicksburg, as it was rumored that the Yankees were about to storm the city. We got into Vicksburg at night, and were ordered up on Snyder’s Bluff. I do not believe any man who was there will ever forget that night, even if he were to live a thousand years. Such thunder, rain and lightning I never saw and heard, before or since. We were ordered not to make a sound, not even so much as a whisper. We could only take a step when the lightning flashed, and then we moved from one tree to another, clinging to the branches to keep from slipping over the bluff. Up at the mouth of the Yazoo we could catch a glimpse of the Yankee gunboat lights.

(Vic’s comment: Patrick’s future brother-in-law was in the Union host below the town).

For the next several nights we were sent down on the levee. The march and long wait were made in absolute silence. The enemy must have suspected that the “Tinth” was waiting to give them a warm reception, for they failed to show up. At intervals “Long Tom” would throw a ball from the top of Snyder’s Bluff up the river to entertain the gunboats.

From Vicksburg we went on a transport to Port Hudson.

Queer things happened on that transport. When we reached Port Hudson, the boat was minus all of its mirrors, knives forks, spoons, blankets, and rations. The captain of the transport reported the matter to Col. McGavock, who ordered his men to fall into line, spread their knapsacks on the ground and open them out, and also to turn their pockets inside out. Colonel McGavock, the officers of the regiment, and the captain of the boat went from one end of the line to the other but not one thing could they find that belonged to the boat. After the search was completed, Col. McGavock made a speech to the captain of the transport, in which he eulogized his regiment, saying that it was made up of honest and brave men, and that as a matter of course, it must have been some other soldiers or thieves that had ransacked the boat. However, Col. McGavock went to the commissary and drew enough rations to supply the captain and his crew until they got back to Vicksburg.

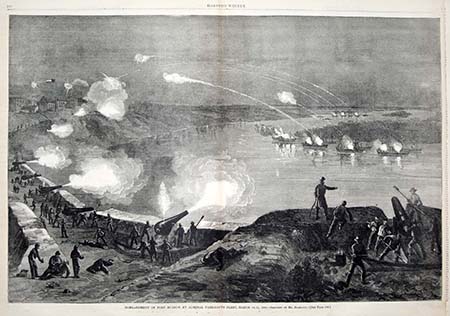

We helped to fortify Port Hudson, and we were there at the bombardment. On the night of the bombardment, we had a pyramid of lumber built up about a mile below the port, right opposite where the gunboats were anchored. We had orders to set fire to the pine knots when the first boat advanced. Two forty-five-gun frigates started up the river at nightfall.

(Union gunboats attempt to run the gauntlet at Port Hudson, from the etching in Haper’s Magazine).

The pine knots were ablaze instantly, and every movement of the fleet was seen by the gunners at the port. The first frigate succeeded in getting past, but she was battered up considerably. The second frigate made an effort to compel the port to surrender, but we poured shot into her at such a rapid rate that she ran out die white flag. We ceased firing at once; and when her commander saw that we had stopped, they began firing on us again. Then the captain commanding the battery ordered the boys to “give ’em red-hot shot.”

The order was obeyed, and the red-hot shot set fire to the frigate, her machinery stopped, and she began to swing round and round. The crew jumped overboard, and we could hear the cries and groans of die wounded and dying.

Admiral Dewey was on that frigate. He was not an admiral then, but be must have been a good swimmer.

Directly the fire reached their ammunition, when bombshells and cartridges began to explode in a grand fusillade. She floated down the river, and the boats of the fleet moved hurriedly in order to give her plenty of room to pass. Several miles below the magazine exploded, and we knew dial the end had come for that frigate. It was a wonderful sight!

The port lay in the shadows, and below it the Mississippi stretched away a veritable stream of fire. Farmers who lived ten miles away told me afterwards that the light was so bright at their places on that night that they could pick up pins in the road. After this disaster, the Yankees decided that it would be best to make an entrance by the back way.

At Port Hudson, Col. McGavock gave me a good round scolding for exposing myself in range of the enemy’s guns and being wantonly reckless. I think he must have had some premonition of his death, for he told me that he was afraid that he would never get back home.”

Tomorrrow: Port Hudson to Raymond

Copyright Vic Socotra 2015

www.vicsocotra.com

Twitter: @jayare303