People Against the Sea

I love it when I get up in the morning, trying to remember that I still need to find the thousands it will cost to get the Panzer back from the tender ministrations of the technical wizards at the Werkstatt Kompanie- and by the time I have consumed a pot of coffee and ingested my two eggs with cheese-topped mushrooms and onions with shredded tri-tip slow-cooked roast I am preparing to renounce my citizenship.

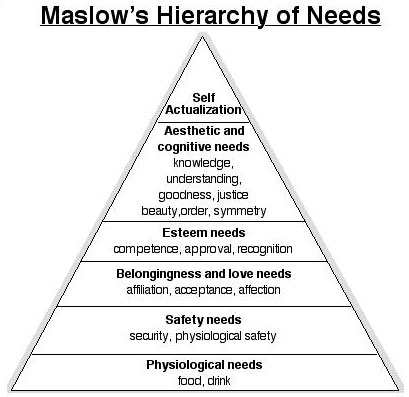

Thankfully, it is so freaking cold out west (17 below!) that I managed to climb right back down Maslow’s hierarchy of needs that I was able to think rationally that life with pavements dry in Arlington, and temperatures hanging above freezing that I consider life to be good. I can worry about self actualization later. You have to be alive to do that.

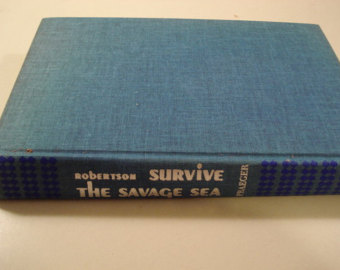

In fact it was good enough to take a look at the little blue volume that Old Jim pushed across the bar toward me at Willow last night. He stumbled across it while looking in his archives for something else, and thought I might find it interesting as a former practitioner of the maritime arts.

Of course, that is not true. We Spooks regarded the primary mission of the surface Navy as being the transportation of our butts from liberty port to liberty port- an enterprise much more typical of the Fleet of the late 1970s and 1980s. The rise of combat operations and increased threat of terrorism have changed all that. But one thing we never worried a great deal about was being cast adrift.

I thumbed through the blue volume with the exquisite it at the bar, noting the “ex libris” notation from 1974, the year after initial publication. The copy resting next to my computer is a first edition.

I got lost in it- it really is a compelling story. The Robertson Family was farming, and Dougal was challenged by one of the their twins to sail around the world. Farming is hard and sometimes thankless work, and that may be why former Merchant Sailor Dougal Robertson did. He sold the semi-functional family farm in rural Staffordshire, England. He took the cash and bought a 1922-vintage 43-foot wooden schooner named the Lucette in the lovely island of Malta, where the Royal Navy’s Med Squadron had once held sway.

The whole thing resonated powerfully with me. When Dougal was planning his adventure I was living on a 1906 Herreshoff Schooner named Neith in the harbor at Beverly, MA. She was a lovely boat with elegant lines, 54 feet LOA, named after the Egyptian Goddess of War and Hunting, and was thinking of several madcap maritime adventures that never came to pass.

Dougal followed through on his, though it is a cautionary tale that I am pleased to not have been aware of at the time. He brought the whole family along on the adventure: wife

Lynn, daughter Anne, son Douglas, and twin sons Neil and Sandy. They sailed through Gibraltar and across the Atlantic to the Caribbean over the next year and a half, and then on to the Panama Canal, where daughter Anne departed the cruise and they picked up a hippy kid named Robin who wanted to hitch-hike across the Pacific.

Bound for the Galapagos Islands, they cruised the exotic isles and then struck out for the Mid-Pacific but did not complete the voyage. On 15 June 1972, Lucette’s graceful hull was holed by a pod of killer whales and went down a couple hundred miles west of the Galapagos.

The six Souls On Board abandoned ship with the same alacrity the Lucette abandoned them. They took to an inflatable boat and a dingy then named Ednamair with enough water for ten days, a bag of onions, a few oranges and lemons, and some sweets.

Which is to say that they were going to die if they did not innovate. Dougal decided to rig an improvised sail and head for the Doldrums where they might collect rainwater in the slack air.

There is a commonality with the two other great stories of navigating open boats in survival situations. The Robertson’s situation continued to disintegrate as the inflatable boat ceased to be so, and forced the relocation of all six to the Ednamair. They survived 38 days by catching turtles, dorados and flying fish for sustenance.

At one point Lynn had to administer enemas with an aluminum tube ripped from a boarding ladder. The mixture she used was rainwater that had been captured in the hull of the dingy, but contaminated with turtle blood and offal. She knew that drinking the mixture would probably poison them, and innovation was the key to survival.

Actually, by the time a passing Japanese Merchant ship picked them up, they had more protein and water than when they started. It is an amazing story, and I am grateful to Jim for reminding me of it. The book was made into a movie, later, which I will look for on Netflix, or perhaps just watch Robert Redford’s new film on the same topic, “All is Lost.” He doesn’t speak much in the film, which is a relief after some of his other recent works.

Like I said, there is a commonality in sagas of being lost at sea: delusion, sunburn, open sores, flying fish blundering into the boat, rainsqualls and the like.

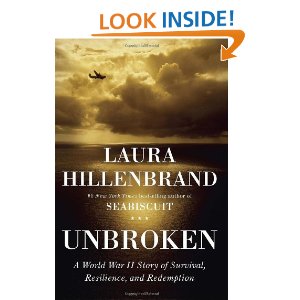

So, actually any of the three books I like best about the experience would suffice. Laura Hillenbrand wrote a marvelous and quite extraordinary tale of former Olympic sprinter Louie Zamperini. If you have not read it, you owe yourself an experience in how far down the hierarchy of needs a person can go and survive, Unbroken.

In the early months of World War II, Louie took off on a search mission for a lost plane out of O’Ahu. Somewhere over the Pacific, the engines on his bomber failed (it was a crappy plane, something we don’t hear much about from the Greatest Generation) and the airplane went into the ocean well short of Palmira Island. Adrift for weeks and across thousands of miles of westward sub-equatorial drift, Louie and two of his crew endured starvation, searing thirst, shark attacks, strafing runs from Japanese aircraft and a typhoon. They finally spotted land and a brief spurt of joy was swiftly replaced by horror that the island was in Japanese hands, and the adventure was only just beginning. Fabulous book and a reminder of the nature of the Empire of the Sun.

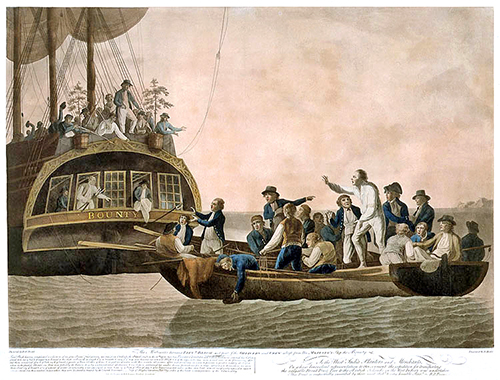

(Contemporary etching of the Mutiny onboard HMS Bounty).

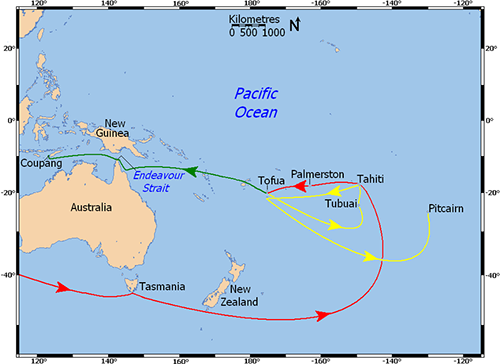

But of course the story I have known about longest, and the one that may stand as the account of the greatest open-boat journey of all time was that commanded by CAPT William Bligh, late of her Majesty’s ship Bounty. I am not talking about the romance of Nordoff and Hall’s account of Men Against the Sea. I am talking about CAPT Bligh’s account: A Narrative of the Mutiny on board His Majesty’s Ship “Bounty”; And The Subsequent Voyage Of Part Of The Crew, In The Ship’s Boat,from Tofoa, One of the Friendly Islands, to Timor, a Dutch Settlement in the East Indies.

If you do not know about that one, you are in for an adventure in disbelief. Six weeks at sea in a 23-foot open boat, riding so low in the water that your hand on the gunwale gets wet from the waves action along the hull. 3.600 miles to cover before landfall, with complete reliance on a man whose name has come to be synonymous with the word tyrant.

(CAPT Bligh’s voyage, courtesy of Wikipedia).

Not altogether true, but that made the Mutiny that much sexier. If I had to make an voyage against the angry sea, that is who I would like to have in command. They say that Dougal Robertson could be a bit of a jerk, too, but all his family lived.

When you are lost at sea, that is a pretty good thing.

Copyright 2014 Vic Socotra

www.vicsocotra.com

Twitter: @jayare303