Raymond

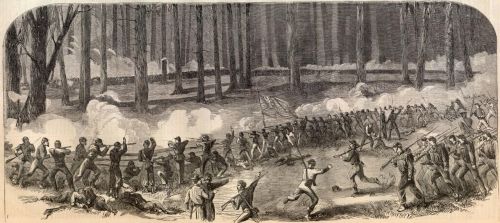

(“Battle of Raymond” by Theodore Davis – Harper’s Weekly, June 13th, 1863, from a sketch by Theodore Davis. Image courtesy Wikipedia).

These have been the words of Patrick Griffin, taken from an address he gave in 1905, some forty-two years after the events he describes. His unit- the Bloody Tinth- had been ordered from Port Hudson to the vicinity to Raymond, just west of Jackson, Mississippi in Hinds County. At his point in the great struggle the Confederates had acquitted themselves well. Back in Culpeper, the forces of Robert E. Lee were preparing tomove North to invade Maryland and Pennsylvania. But in the West, the implacable U.S. Grant was determined to seize Vicksburg and truncate the lines of communication between the rebelling states.

The Battle of Raymond was fought on May 12, 1863, less than a month before the Army of Northern Virginia would come to grief at Gettysburg. The bitter fight pitted elements of Grant’s Army of the Tennessee against Lt. Gen John C. Pemberton’s Department of the Mississippi and East Louisiana. The Confederates failed to prevent the Federal troops from reaching the Southern Railroad, effectively isolating Vicksburg to the north and preventing Confederate reinforcements and logistic supplies from reaching the forces in the field.

During the morning of the 12th, the Confederates enjoyed a two-to-one advantage in numbers, as they faced off across Fourteen Mile Creek against a single Federal brigade. However, as morning turned to noon and the Confederates waited in ambush, the remainder of the Federal division secretly deployed into the fields beside the brigade, giving the Union troops a three to one advantage in numbers and a seven to one advantage in artillery. In comparison with the major engagements in Virginia, this battle produced relatively few casualties: Union casualties at Raymond were 68 killed, 341 wounded, and 37 missing. The Confederate casualties were nearly double: 100 killed, 305 wounded, and 415 captured. That is where things get personal, since one of the dead was the Cavalier Commander of the Bloody Tinth, and one of the captured was kin.

I will let him tell you about it in a moment, but this small battle had an inordinately large impact on the Vicksburg Campaign. Union interdiction of the railroad interrupted Pemberton’s attempt to further consolidate his forces and prevented him from linking up with his boss, General Joe Johnson, and forced the next encounter a few days later at Champion Hill. It also burnished the reputation of General Grant, who would soon be called by President Lincoln to carry the war to victory in the East.

Great-Great Uncle Patrick paused at the podium and took a sip of water to wet his whistle, and surveryed the crowd before him in the packed hall. He began again, saying:

“From Port Hudson we went to Jackson and then west to Raymond. We camped outside of Raymond on the night of May 11th 1863, and the next morning we marched through the town. The ladies who lived there came to meet us with baskets of pies, cakes, and good things. They were even kind enough to bring buckets of water and dippers, and many a soldier blessed them as they passed down die ranks.

A hushed stillness seemed to hover over the world that morning. A mile or so from town we sighted die enemy. We had marched up on a rise and were out in the open, and they were in the woods about one hundred yards in our front when they began to fire on us. I was standing about two paces in the rear of die line and Col. McGavock was standing about four paces in my rear. We had been under fire about twenty minutes, when I heard a ball strike something behind me. I have a dim remembrance of calling to God. It was my Colonel. He was about to fall. I caught him and eased him down with his head in die shadow of a little bush.

I knew he was going, and asked him if he had any message for his mother. His answer was: “Griffin, take care of me! Griffin, take care of me!” I put my canteen to his lips, but he was not conscious. He was shot through the left breast, and did not live more than five minutes.

When I saw that he was dead, I placed his head well in the shade and stepped back into position. The field officers being at the ends of the line, I had no opportunity to report to them that he had been killed.

The orders came in quick succession, “Left flank by file left!” “Double-quick, march!” and then “By the right flank!” and the next command was drowned out by the Rebel yell. We ‘charged the Yankees and chased them into the woods. At the edge of the woods the order was given to “Double-quick, march” and we were halted again under the protection of a little hill. On the top of this hill there was an old log cabin, and twenty of our fellows went into it to fire through the chinks in the wall at the enemy.

Not one of these men was ever seen alive again. We had to stand and see them shot down like rats in a hole. Every time one of them attempted to get away a bluecoat in the woods brought him down. I remember one member of my company, John Corbett, called to me to come and get his money for his wife. He said that he was wounded and dying. Any man who attempted to climb that hill must die also.

Lord, we learned what war meant that day.

While we were halted there, I met Lieut. Col. Grace and asked him if he knew that Col. McGavock had been killed when the battle first began. “My God!” he exclaimed, as though he hardly believed it I assured him that it was true. He then told me that the order was to get out of there the best way we could. I explained to him that I wanted to go back after the Colonel’s body, but he said that it was out of the question. I insisted that I had given my promise to the Colonel to take care of him, and that I was going to do it to the best of my ability, whatever happened. He replied that if I went it would be at my own risk.

I got two of the members of my company to volunteer to go with me. We found the body just where I had left it. We picked him up tenderly and started toward town. I hope and trust that God will never let me find a road so long and sorrowful again. Capt. George Diggons and Capt James Kirkman were the only members among the wounded of my regiment who were able to get away from the battlefield. The Confederates were retreating rapidly, and we were not far on the way when the Yanks came in sight. As soon as my two comrades saw them, they let loose of the Colonel’s body and started to run, but I drew my pistol and told them: they would have to die by him; but later, seeing there was no possible chance of escape, I told them they could go and I would stay with him.

The Yanks came rushing along, some of them stopping long enough to make some jeering, sarcastic remark, but they could not shove the iron any farther into my heart that day. It was fully two hours before the rear guard came up. The officer in charge was an Irishman, and I want to say right here that I am convinced that if ever there was a good Yankee he must have been Irish. I heard the fellows call him Capt McGuire, and I learned that he came from the same county in Ireland- Galway- my parents came from. He asked me who was this officer I was holding in my arms; and when I told him that it was my own colonel, McGavock— an Irish name—he took it for granted that the Colonel was a “townie” of mine, and he ordered his men to place the body in one of the army wagons.

The Colonel was free for evermore, and I was the lonesomest, saddest of prisoners.

When we got into town, night had fallen. We were taken to a hotel that had been vacated by its owner and was being used as a prison by the Yankees. McGuire promised to try to procure a parole for me for a few days. The Colonel’s body was placed upon the porch at the hotel and remained there till morning. Although I was literally worn out I did not sleep a wink that night The next morning, Capt. McGuire came with a two days’ parole for me. I got a carpenter and asked him to make a box coffin, for which I paid him twenty dollars.

My fellow-prisoners assisted me in any way they possibly could. Many friendly hands were to help me place the Colonel’s body in the rude coffin. I hired a wagon in town, and got Capt. McGuire’s permission to have all the Confederate prisoners follow the body to the grave. We had quite an imposing procession, with, of course, Yankee guards along. I had the grave marked and called the attention of several of the people of Raymond lo its location, so that his people would have no trouble finding him when they came to bear him back to Tennessee.

When the funeral was over, we marched to the hotel prison. Although I was only a boy then, the memory of the miserable loneliness of that night has never been quite blotted out in the years that have intervened. No man has ever come across life’s pathway to fill McGavock’s place in my heart.

Copyright 2015 Vic Socotra

www.vicsocotra.com

Twitter: @jayare303