Remembrance (of Things Past)

(This image of Building 213 at the Washington Navy Yard is an overhead image with one-meter resolution, which is to say that a skilled photo interpreter can distinguish objects measuring about a yard in length or width. Such a capability was pretty cool, back in the day, particularly when you could not fly over head to take the picture. Photo NGA.)

I was not reading Proust. Heck, I am not reading much of anything these days except this unending cascade of digital mail, but it The Day got me again. I thought the Anniversary of the sneak attack on Pearl was tomorrow, or Monday or something. I told you that I wanted to tell the story of a featureless building down at the Washington Navy Yard that is going to be destroyed pretty much without comment.

Mac Showers played a role in what happened in that building. I will have to go back through my cocktail-napkin notes. His work in targeting the Empire of Japan for Curtis LeMay’s B-29s required aerial photographic data on which to base target nominations and re-strike options. LeMay was not getting the information he needed from the Air Corps Strategic guys back in DC, and on the sly, used the target deck generated by Mac and his comrades at the forward CINCPAC HQ on Guam.

Anyway, I was thinking about Mac this morning when I realized that the day was here, and I needed to acknowledge the sacrifice that came from the singular moment when the first wave of fifty Nakajima BN5 Kate bombers swept over the imposing green wall of the Ko’olau Mountains to usher in an entirely new world.

Mac described his arrival at Pearl in February of 1942 many times. He was not there for the attack, of course, though the imposing bulk of USS Nevada was resting on the bottom near Hospital Point, and the big ships were still on the bottom along Battleship Row where they were sunk at their moorings.

That was the alpha of his career in our business, and targeting from the air was a huge component of it, whether the targets were in the old Soviet Union, or the PRC or Vietnam. That is what brings Mac’s story around to Building 213, the featureless six story white building at the Yard where so much secret history occurred.

The leap from military photo interpretation to strategic photo intelligence, augmented by Communications Intelligence was pioneered by Mac and his comrades in the Estimates section of JICPOA. It rose again in 1950 at the new Central Intelligence Agency. Mac told me about one of the early iterations, located in an anonymous office space above a car dealership in the District. I will have to check my notes, since I was going to try to find it someday. An official, though redacted account of the early days can be found here.

The days of high speed photo aircraft making simulated runs at Soviet coastal targets provided images for exploitation; later improvements included the celebrated Dragon Lady U-2 and the remarkable SR-71 Blackbird.

And of course the early Corona imaging satellites and their successors, the electro-optical systems that my Uncle worked on. I have a framed picture at the farm from one of the Ranger survey missions to the moon. It is an otherwise unremarkable image of the lunar surface, except for one curious thing: the raster scans that make up the image mean that no film ever returned from the moon. Rather, the picture was transmitted digitally back to earth in a stream before impact on the pumice-gray surface.

Uncle Jim winked at me when he told me about it. Peaceful space exploration always served a dual-use function. With the advent of electro-optical transmission, images from orbit (not of the moon, hahaha) could be captured and exploited in near real time for timely strategic intelligence of military movements, construction and shipbuilding.

That is what surprised me when I was sitting waiting for Ben, my Tunisian barber ,this week. He still had a guy in the chair and I sat down in the waiting area and picked up the Metro Section of the Post. There was an account of a big empty building at the Navy Yard that was temporarily being used for an open-air art project.

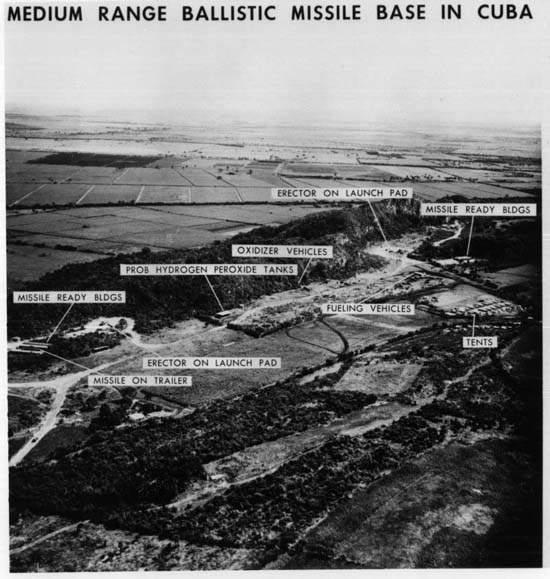

I blinked in amazement. It was Building 213, a place that should be remembered with the same sort of reverence as Ford Island at Pearl Harbor. The things that were done at the Yard still boggle the mind. The Cuban Missile Crisis. The Vietnam War. The Single Integrated Operation Plan (the nuclear SIOP material) that mapped the way to nuclear Armageddon.

The Pizza Trucks that sped away from the building, surrounded by barbed wire each morning, rigid two-man control for the imagery flats that looked vaguely like delivery pizzas to Spook Agencies all over the city.

Unlike Pearl Harbor, where I lived and the kids were born, I was only at Building 213 once. The visit was to examine another of the series of technological miracles that marked the long chilly struggle: a machine that enabled the digital manipulation of the digital images. The machine was so powerful that the electronic signature could be monitored dozens of feet away, through concrete walls, and thus the machine was housed in a copper-lined room.

The old-fashioned light tables used by photo interpreters since the dawn of aerial photography were gone, and Building 213 moved into the modern digital world.

The Post article did not reference the building number, nor the people who had worked there for decades. Those were the days when the area around the Yard was lower than slum, and the only activity outside the wall was at the liquor store across M Street. Gunshots could be heard most mornings, and you could not blame the Federal guards at the checkpoints in the barbed wire from being a little edgy.

There were huge secrets to be protected, and some of the most highly cleared personnel in the government routinely ran the gauntlet to go to work, examining the target decks of the adversary each day for indications and warnings of the end of the world.

In that context, the Post casually mentioned that Building 213 is now itself not long for the world. The last inheritor of the photo-imaging mission was the National Geospatial Intelligence Agency (NGA). They moved out last year for their palatial new headquarters at Fort Belvoir. It is an impressive building with a soaring seven story atrium and fancy paneling. It is the last of the Post 9/11 palaces erected to serve the new National Security State.

Building 213 was stripped of top secret communications and satellite gear, and all the machines that displayed the images of places the spies could not safely go. Then it was de-SCIFed and the metal ripped out until there was only bare concrete and the guards walked away without looking back.

The Post breezily reported that the building would be razed sometime in the next year or so. Rumor is that it might be replaced by a gourmet supermarket like a Whole Foods Store. That part of the SE District has been waiting for something like that for a long time.

Still, I found it sort of amazing that no one is remembering what was done in that building, and its role in the long Cold War and the hot ones since.

Since this is a day to remember Pearl Harbor, we need to do that to honor the dead of the Pacific War that began there. But the peaceful harbor in which USS Arizona still weeps drops of fuel oil from her corroding bunkers, with USS Missouri’s imposing bulk anchored astern will be there next year. They are the Alpha and Omega of the struggle, and an inspiration.

Building 213 will not be there. The secret history of it will vanish as completely as the structure. Pity really. People should remember what was done there.

(National Photographic Interpretation Center annotated image of a Soviet missile site in Cuba, 1961. Work similar to this was done at Building 213 for sixty years. Photo CIA).

Copyright 2013 Vic Socotra

www.vicsocotra.com

Twitter: @jayare303