Staff Work

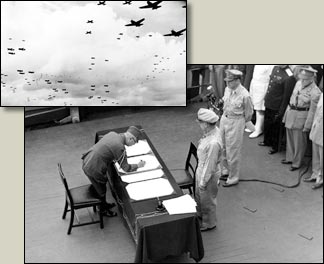

(Mac in 1945. Photo courtesy the Admiral)

Sorry. No time to follow up on the story this morning. I am pinned to the computer waiting on an input from my able Subcontracting officer, based on some work that went on past midnight last night. My input was going to be about young Major Sweeney, the Air Corps pilot who dropped the second of the Gadgets, the products of the most expensive project ever conducted by the human race, an enterprise that exceeded that those of the Pharaohs and their pyramids in terms of public treasure.

It actually was sort of casual, the mission to Nagasaki. Col. Tibbitt, the squadron commander, had electrified the world with the mission of the Enola Gay. By contrast, the follow-on mission flown by Chuck Sweeney’s crew has been described as “technically botched,” since it missed the primary target of Kokura due to smoke cover (ever heard of it?). Instead, the city of Nagasaki died.

Sweeney was low on fuel by the time he eventually got the B-29 Bockscar back to Okinawa, but it did not matter. The war was effectively over. Still, it is interesting that half of all of the Manhattan Project’s considerable labor was rendered an afterthought, suitable for delivery by a Major.

Anyway, I was thinking about that yesterday, and this morning, hunched over the computer waiting to do something else. I remembered talking to Mac Showers about this a couple years ago, those moments when one world ended and another began.

I had a hard time keeping up with the Admiral. He was 90 then, and I was just a bit more than thirty years younger. He had the life force: I don’t know what it is, but you could see it in his merry eyes.

I look in the mirror most mornings and see only blear in mine.

It was past all our bedtimes, but he had escorted all of us at the dinner table of the bustling Willow restaurant back to 1945, and being there with him it was hard to let it go. It can be a little disconcerting.

If you have read the Time Traveler’s Wife you will understand the ability Mac has to transport you across space and time. I have to keep the notes on my cocktail napkin numbered, since earlier in the dinner we had visited 1955, jumping easily between the decades, and the creation of target folders for the SPAD drivers to study before launching against the Soviet Union with nuclear weapons.

It sounds preposterous now, but that was the case when the Admiral arrived at the FIRST Fleet and began to survey how training was being done to support the training mission for units going forward to the Western Pacific.

The Navy had fought hard to be included in the Single Integrated Operational Plan, the master scheme for the attack on the Evil Empire, should it have come to that. The SIOP (pronounced “sy-op”) was an esoteric and highly political document that purported to de-conflict Air Force and Navy strike operations in the event that the balloon went up. It required a lot of staff work.

The Admiral was disconcerted to find that there were no materials to assist the dauntless men in their flying machines on their way to Armageddon. He fixed the problem in his tour by establishing a new staff to prepare highly sensitive target folders. There were no satellite pictures to help, as there were in my day, but at least the pilots had some some way-points on the route to hell.

It is a magical thing, talking to someone else who was in the same very sensitive line of business a long, long time ago.

With Mac, it is as fresh as if it happened yesterday. The years fall away, and you can feel the presence of others, dead now, crowd around holding glasses of whiskey and nodding. The Admiral is their emissary, their guide between the worlds.

I could tell you where we were in the course of drinks and dinner, but mostly it was in 1945, since so much of our present rests on the foundation of what happened that year.

The Admiral recalls that the SPAD, the vaunted AD-1 Skyraider that the Douglas Company built for the Navy that my Dad flew, was designed so that it’s internal bomb-bay could accommodate the dimensions of the atomic bomb.

I scratched my head at that. The Bomb was one of the biggest secrets in the world at the time, and certainly it would not have been disclosed to the designers at their drawing tables at the Douglas Corporation. Or perhaps it was just a grim-faced staff officer in dress khakis who showed up one day after lunch, and spread his arms “just so,” and told them it had to be that way, “just shut up and do it, you have no need to know why.”

The Admiral was just a pup then, twenty-six and a Lieutenant on the staff, but filled with vinegar then as he is now. The war had moved mo west. Guam fell in early August, 1944. Nimitz arrived on the doomed USS Indianapolis, and directed his staff relocate from Pearl to commence work there on the 15th of January.

Mac mentioned that the Marines were still catching eighty or more of the former enemy a day. They were hungry out there in the jungle, and sometimes the Marines killed them in the night, as the hungry soldiers scavenged for American food. The staff officers would walk by the bodies on the way to work in the morning on CINCPAC Hill.

They were planning the end game of the war, as best they could conceive it. The over-arching plan was called DOWNFALL, and included two major landings in the Home Islands. One would be led by General MacArthur in Kyshu to the south, code-named OYLMPIC, and a second one under the command of Fleet Admiral Nimitz on the Kanto Plain near Tokyo called CORONET.

“Why two invasions,” you ask?

One for the Army, and one for the Navy, silly. They don’t call it inter-service rivalry for nothing.

The Admiral was briefing events cribbed out of the Foreign Broadcast Intercept Service, which is called something a lot less ominous these days. That was really a cover, though, since his unclassified briefings were informed by highly secret decrypted intercepts of military and diplomatic communications.

If you are like me, history forms a jumble in the mental attic. For a lot of folks, amiable chowder-heads, it isn’t even a jumble. It just doesn’t exist. Here is what was happening that chaotic year of 1945, as the Admiral was briefing and planning:

Soldiers and Marines landed on Okinawa in March. President Roosevelt died on April 12th. The Nazis quit in May, and the troops were told to prepare for the invasion of Japan. The new fellow, Harry Truman, was informed that there was something being worked on, something big. Major combat operations were concluded on Okinawa in June, though scattered resistance continued.

The Scientists of the Manhattan District Project did not know if their bomb would really work, or if it would consume the atmosphere if it did. It was not tested until July 16th of 1945, as the Gadget was assembled at the hijacked McDonald Ranch and then trucked to the tower where the Los Alamos scientists predicted it would probably detonate with great force.

The CINCPAC Fleet Gunnery Officer, CAPT Tom Hill, was sent to observe the event, and he brought a highly-classified film clip back to Guam to show Fleet Admiral Nimitz, for his eyes only.

Nimitz pursed his lips, and kept his own council at the news as his staff planned the end.

Truman sent a question through his Joint Chiefs, once he knew what they had. How many Americans were likely to die in the invasions?

It was a logical question, for a man who had options that others (except Uncle Joe Stalin) did not know about. In the Philippines and on Guam the planners paused in their deliberations and made calculations.

MacArthur’s people in Manila low-balled the estimate. Maybe a quarter million, they said, ignoring the evidence of the communications intercepts that stated plainly that the Japanese knew where the landings would be, and that everyone, man, woman and child, would die to stop them.

The Admiral’s team, headed by Ground Analyst Hal Leathers looked at the evidence from the defense of Okinawa, and calculated that it might take more than a couple million casualties to secure the capital.

MacArthur desperately wanted to command the invasion, and damn the cost, in treasure and lives. That was his way. It was like his insistence on receiving the Congressional Medal of Honor for good staff work so that he could join his Dad as the only Father-son combination ever to win the highest military honor in the land.

There was discussion at the time back in Washington of considering Dugout Doug for promotion to a special “super rank” of General of the Armies, so as to be granted operational authority over other five star officers like Admiral Nimitz. Thank God the plans went forward as they did.

MacArthur would have been a Caesar in reality then.

The story has been told of the days the world turned more acutely on its axis than normal. A-bombs fell on the 6th and 9th of August. I commend to you the account of the second strike on Nagasaki, and the comedy of errors recounted by Major Sweeny in the Super Fort Bockscar, which resulted in an emergency landing on Iwo Jima to refuel and make it back to Tinian from the second most important mission the Air Force ever flew.

Maybe it didn’t matter. Both of the weapons had worked as advertised, hundreds of thousands died, but not tens of millions which might have occurred if that astonishingly brutal path had not been chosen.

General MacArthur arrived at Atusgi Air Base on the 30th of August, the strangest month in the strangest year in human affairs to that date. I used to stay at Atsugi periodically and marveled at the revetments of old gray concrete that protected Saburo Sakai’s Zero fighters still ring the ends of the field.

They say there is much more still below in twelve great caverns carved out by the industrious Japanese, but it is too dangerous to go down there even after all these years, since traps were set with deadly efficiency, and now all those who set them are gone.

By the 2nd of September, the Allied Fleet was in Tokyo Bay to take the surrender.

(Surrender and fly-over. Photo montage courtesy University of Nebraska based on official USN Navy Photos)

Being so junior at the time, Mac stayed behind on Guam when Nimitz and four of his officers went to attend. He was there two days later, on a courier run, dispatched by his boss Captain Eddie Layton on an improvised and probably bogus mission to have an see what they had accomplished.

He landed in a seaplane next to a tender moored in the Sagami-wan in the late afternoon, and a jeep took him to Yokohama where MacArthur’s staff was preparing the Occupation. For perhaps the only time in history, there was no traffic on Route 16 north from Yokosuka to Yokohama. There were crowds of Japanese on both sides of the road, looking at the jeep impassively as it passed.

He arrived in the dark, and handed over his briefcase. By the time he got back to Yoko, there was only time to trade a bottle of Three Feathers Whiskey from the wine-mess on Guam to a young Marine for one of three remaining battle flags liberated by the Marines from the only Japanese ship that was still in the harbor, the heavy cruiser IJN Nagato.

Then it was on a motor-whaleboat to the seaplane tender for the flight in the morning.

(Tokyo at Peace. US Air Force photo)

“After we lifted out of the gray waters of the bay, the pilot did two long circles around the blasted capital before heading southeast for Guam. All the wooden buildings were ash, and only a few buildings stood in lonely isolation near the Imperial Palace. You could smell it.”

“So, you got back to Guam and what was it like, Sir? Having it over and done with such abruptness? It must have been surreal. When did you go home?”

“We were told we were to clean out our desks. We were flying on the Staff C-54 back to Pearl, direct, with a brief stop for fuel at Kwajalein Atoll.”

“You must have accumulated enough points to be among the first to go home, back to CONUS, the Land of the Big PX,” I said.

Mac dabbed his lips with one of the snowy white Willow napkins. “Well, I did have a lot of points. More than most. But that is another story,” he said. I waved to the waitress, suddenly realizing I needed another napkin and either a brandy or a cup of coffee.

Or more likely, all three.

Copyright 2010/2013 Vic Socotra

www.vicsocotra.com