Storm of the Century (Again)

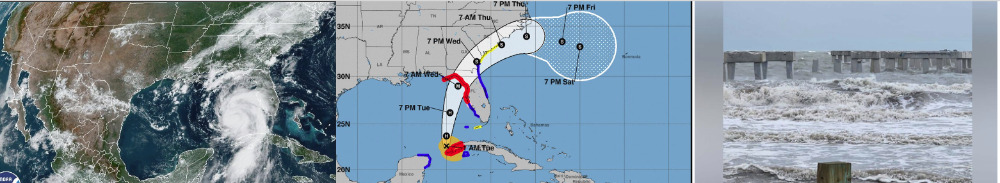

(At the attachment is Hurricane Idalia, depicted from NOAA orbital sensors at left, in the Metro map track in the middle, and a view from the Tampa Bay beach down in Florida. This storm is part of a seasonal cavalcade of gray blowing energy. Last night, with the storm intensifying, we “heard the words.” Again. Those would be the ones that say:“Storm of the Century.” That makes this a meteorologic time machine, since Hurricane Hilary last week in San Diego was another century’s worth of occasional fury. In between there was a violent Mid-western storm, not hurricane, that pulverized parts of Michigan. It was violent enough to characterize as a once-per-century event! It seems we have been saying “third times the charm!” fairly frequently on this storm season!)

We have heard about “Storms of the Century” before, and since we are now creaking with age, it is not uncommon to have events that happen infrequently seem oddly routine. We took a poll out on The Patio and can’t vote for Hilary or Idalia as being contenders for most spectacular of the last century. Our personal vote for the most impressive storm in the several decades we have had the opportunity to observe goes to Super Typhoon Tip in 1979. That is only about a half century ago, but Typhoon Tip showed us gray swirling water shooting up into the vertical over the bow of the warship USS Midway.

She is still afloat in a pride-of-place position on the CONUS side of the San Diego Harbor. When we knew her as a living ship (and residence) we were in Yokosuka harbor across the broad Pacific. It was an interesting arrangement, since we were assigned to one of the aviation squadrons stocked with a dozen F-4 Phantom II’s. The aircrews and maintenance folks in The Vigilantes of VF-151 got quarters ashore when we were in port and even had allowance for family quarters.

That was not true for the Air Intelligence staff. We had the clearances to manage the nuclear command and control watch, and that tied us to a physical presence on the ship, tied to Main Comm. We ground-pounders in the airwing squadrons were stuck, as a group, and could not enjoy the pleasures of the central Kanto Plain as often as our squadron buddies.

We were neither fish nor fowl; not essential to flight operations while on the beach, and not exactly ship’s company. It was an arrangement that permitted all sorts of mischief when there was nothing meteorologic of interest going on. It got much more immediate when the storm winds started to blow.

In the case of Typhoon Tip, that particular storm of the century, our jets had to scatter before the rising storm of the Pacific, and we would be tied to the steel of the ship as they ordered us to sea for our best shot at storm avoidance.

“Tip” was considered to be the most intense and largest tropical cyclone ever to form, more intense even than the legendary Typhoon Cobra, the 1944 storm described in “The Caine Mutiny.” Vice Admiral “Bull” Halsey lost three destroyers from his Task Force 38 to the roaring winds and cascading waves. The date of that storm puts Cobra in contention for storm of a busy century with the two we have had in the last week.

Admiral Halsey later said the storm was as hard on his task force as a heavy engagement with the enemy. His surviving ships reported taking 70-degree rolls.

Think about that for a moment, would you? The ships that did not tip all the way to 90 degrees, and ultimately beyond that, right-angled to the towering swells. Angry saltwater cascaded down into the stacks and flooded the engine rooms and the lean gray ships foundered, and then just kept rolling.

In the case of Typhoon Tip, we had no particular fear of anything like that. Tip formed in the northwestern Pacific in early October of 1979 as a tropical depression. Over the following week, it intensified to tropical storm and finally typhoon strength. On October 11th the pressure dropped 98 Millibars, from 996 to 898, and became Super Typhoon Tip. Circulation reached a record-setting diameter of 1,350 miles with gale-force winds extending 675 miles from the Typhoon’s eye.

We were sitting in Yokosuka as the storm grew and were joined by a new escort ship- USS Bainbridge, a nuclear cruiser. The intent had been to ride out the storm in the protected waters if the Sagami Wan, but there were other external factors that needed to be addressed. Those included the magnitude of the storm and the fact that word was getting around that a nuclear warship was in port.

It is funny that this morning, some 44 years later, the Japanese Maritime Self Defense Forces (JMSDF) are looking to establish their own nuclear deterrent against Russia, China and North Korea. It was simpler back then. We just went to sea.

It was the first time I saw the plates move across the wardroom table of their own volition. To experience Tip’s fury, we ventured up to the catwalk on the ship’s island to watch the steel of the bow rise with slow majesty before falling back under sheets of gray and green water. Tip’s heavy seas were punishing. They carried away the whisker antennas along the catwalks below the flight deck way forward. There was actually a brief weightless moment at the top of the arc of movement.

Here is what made Tip something for the century-long list of honor (and horror): on the 12th she generated 190 mph winds off the lowest barometric pressure ever recorded for an atropical cyclone. Got it? We are talking 870 millibars.

We were mobile and zigged and zagged south from Japan to the Philippines and the usual change of dangers provided by the establishments on Magsaysay Boulevard in Olongapo.

Tip left some marks of fury: the agricultural and fishing industries were ravaged and sixty-eight people died. That is a smaller number than the wildfires claimed out on Maui, but we have not seen a final accounting of what the fires did to the folks who were trapped there.

Tip killed something else, too. It was something that had been in place since 1945. The primary transmitting tower of the Far East Network (FEN) was at Camp Drake, near Tokyo. It broadcast 10,000 watts of rock and roll on AM 810, and carried language lessons and all sorts of daily Americana to keep the troops from getting homesick.

Typhoon Tip knocked down the transmitting tower, and that was the end of broadcasting America to the Japanese. Thereafter, only low-power broadcasts were permitted, and television transitioned from broadcast to cable delivery, only to be seen on the bases, or by direct satellite delivery.

We can safely argue that Tip might still be called the “Storm of the Century” despite what they say about Hilary or Idalia. It was a weather event that was a social tipping point. After Tip roared through and knocked down the broadcast towers, never again did a Japanese person approach us to ask, in decent American English, what we thought about Casey Kassem’s American Top Forty Count Down.

That was October of 1979, and our candidate for Storm of the Century!

Copyright 2023 Vic Socotra

www.vicsocotra.com