Sydney

25 April 2005

There are some other things I could talk about this morning, but I am going to let the smart people read the tea-leaves, as someone said yesterday. This remarkable situation will either sort itself out or it won’t. I prefer to contemplate times when things made sense in the great cities on the shores of the broad Pacific. We have talked about some of them lately.

My favorites include San Francisco on the American side, Hong Kong and Shanghai in the South China Sea, and sun-drenched Sydney on the Tasman Sea. These towns all have something in common, a certain raffish sophistication that is quite appealing. Sydney is something special, though.

It was ANZAC day in 1996 that I remember vividly, the second of three visits to confer with our Allies on matters of great import.

I have approached Australia from west and east, from the newer and older directions. The place being upside down, it was entirely right that my first visit was to the newer coast, at Perth, the second time to the landing beaches of the First Fleet at Sydney, and the third time for a month in the capital of Canberra where I actually saw it snow in the middle of the summer back up north.

I liked all three cities, though they have flavors as individual as their beers. Sydney is where the rag-tag band of adventurers and convicts ended their journey after Transportation, a universe away from the gray skies of Merry Olde. There on the desolate coast they began something entirely new.

The annual tri-lateral Australia-Canada-U.S. Intelligence Exchange was hosted by the Aussies the last time I was there. Due to some intentionally poor planning on my part, we could not connect with the once-per-week military flight that went Down Under. Consequently, we had to fly commercial air, but the conference was planned around the military schedule and we had to remain over the weekend at our hotel in the wild and wooly King’s Cross district of Sydney.

We established our own beach-head at the side-walk café in front of the steak house where the road bends to the left and begins the gentle decent to the harbor. We’d watch the women and drink the fine strong Australian beer for hours. The women were pretty, not that any of us were looking. We were too old for the frenzy I remembered from my first visit to Perth, twenty years before.

On that visit, the Royal Australian Navy hosted us that first night of the port visit, at a gymnasium. We were in whites and the beer was in kegs and long metal trays were placed on the floor to accept our cigarette-butts. And the women flowed in through the door, seemingly all wanting a Yank for the week. By the time we got downtown that night, I saw a guy from the sister fighter squadron ride by in the passenger’s seat of a shiny Rolls. The woman who was driving apparently had an appreciation for speed.

It was a grand time, far too busy to sleep, and predictably we met the loveliest woman in town about an hour before we had to leave Fleet Landing to return to the ship. She was a French-Vietnamese woman who combined the best of east and west, and spoke with a lilting Aussie accent. The crowd of officers gawking at her behind the bar was at least five deep.

The three visits encompass the arc of time from youth to age. It was enough on the trip to Sydney to visit to sit and watch the carnival of King’s Cross to sweep by, and marvel at it. At the time, I was still in the process of destroying the cartilage in my knees, and we would rise just before dawn to go jogging. King’s Cross is like San Francisco. We were just starting the day and the hookers and transvestites were headed home.

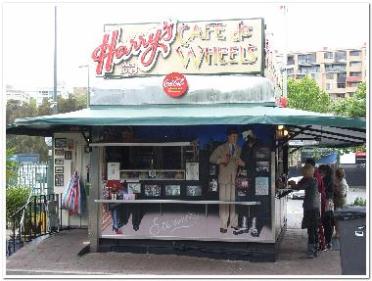

Regardless of the hour, Harry’s Café de Wheels down by the Naval base was always open. We ran down to get coffee. Even at that hour there was a crowd, munching those strange sausages on elongated buns, or the signature pies, filled with mashed green peas.

The trailer is an elongated building made of corrugated metal. There was a little awning that jutted out over the counter area, but otherwise the place was completely open to the elements. In the dark, even with the glow of the lights of the city, you could see the Southern Cross.

In keeping with the name, the diner appeared to have been mobile, at one point, but it had apparently put down roots and would never move again. They told us the tradition of mashed pea-pies with gravy served from trailers apparently goes back to the 1870s, and some purists sniff that the food at Harry’s is awful.

A framed picture of Frank Sinatra enjoying one of the pies hung on the wall under the overhang. I agree with Frank. Harry’s is a fine place to look at the water, and stretch the legs.

The diner is behind some warehouses, near the place where the First Fleet arrived. They could have used a visit to Harry’s. They had been at sea for eight months, and had 750 prisoners consigned to colonize a place called Botany Bay. Captain Arthur Phillip, Royal Navy, was in command of the riff-raff, who had been sentenced to establish the first European settlement on Australian soil.

It is considered a note of local distinction to be descended from the line of one of the first convicts, a sort of austral Mayflower cruise.

The waterfront at Sydney is something special. After a cup of coffee, we continued to jog along the waterfront. As guests of the RAN, we had access to the Naval base itself, could run past the piers with the sea-foam colored warships and the quaint Victorian buildings.

The architecture makes these former Royal Navy bases post cards from the old Empire, all built from the same blueprints, whether they are in Port Arthur or Bombay. With the light coming up, our pace slowed to a walk, and then to a wander.

From the Naval Base you can look both out to broad bay and to the narrows, where Mrs. Macquarie’s Chair was carved out of a rock ledge for Governor Lachlan Macquarie’s wife, Elizabeth. The Opera House sits in splendid architectural cacophony across a little bay behind it, and beyond that the coat-hanger shape of the Harbor Bridge looms behind it near The Rocks neighborhood.

That morning, I turned back to look up the bay, wondering if we had enough time to keep walking, or whether we had to pick up the pace. I noticed that above the path a little glass-and-steel pagoda had been placed on the rocks. It was an old object, as things go here, and I climbed up to examine what purpose it served.

Beneath the cloudy glass were letters carved into the rock, graffiti left by the sailors of the First Fleet, first white people to come here, two-hundred and fifty years before. According to the little plaque on the pagoda, the runes are initials of the sailors and the name of their ship. There has been no change in sailors, from the days of sail to steam. A bottle of rum and pocketknife can provide hours of constructive fun.

Later, showered and in uniform, we discussed many topics of mutual importance at the conference, regional security issues, and the looming impact of China to the north. The gently expressed frustration of allies trying to keep aging equipment compatible with the gear that we seemed to change every year or two.

On Sunday, a day with no social obligations, I spent a moment in the blinding sunshine at the ANZAC Memorial.

The Australia-New Zealand Army Corps is the touchstone of the two nations. You can say, fairly, I think, that they were colonies before the Corps was raised, and after the flower of their youth was savaged by the Turks under the cliffs of Gallipoli, they grew up.

(Image from a photograph courtesy of ANZAC Memorial, Sydney).

It was traumatic, but the anger at the loss of life forged an identity that was completely independent from that of overseas British citizens. Inside, in the silence under the dome, a bronze statue of a nude young man is draped on a marble base. With bayonets, he lies prostrate, eyes looking up not in supplication, but resignation. Light floods his form.

This is the place the Aussies commemorate the losses at Gallipoli, far from the sheep stations and gold mines of the Outback, and the sandy beaches. Winston Churchill sent the diggers and Kiwis of the ANZAC Corps there to be slaughtered there in the “soft underbelly” of the Triple Entente in 1915. It is not fair to blame Winston for the execution. The idea was good enough, in its way. Regrettably, it was not enough to have an idea. There had to be logistics and planning, and there was little of that.

We had a whole block of study on the Gallipoli disaster at the War College, an exercise in understanding how badly something can go with poor planning. Our instructor was a retired Colonel of Marines who had walked the ground personally. He had a slide presentation that conveyed the horror of that battlefield, the attackers huddled at the base of the cliffs with the Turks shooting down on them. The soldiers- Diggers they called themselves- lived in dugouts to avoid the snipers. They could not avoid the dysentery and criminally bad leadership.

The Turks were brave, and their German advisors were crisply efficient at killing the members of the ANZAC Corps.

As a result, the Aussies and Kiwis have an attitude. They were still pissed at the Pommy bastards who sent them in eighty years later. For context, Australia on that day had only 12 million inhabitants. In 1915, there were considerably fewer. And what they gave up under those highlands was enormous in its per capita cost. Britain took the brunt of the casualties, over 120,000 of them, with 25,000 dead. But the number of the dead and wounded for the ANZAC was devastating for the colonies. Australian wounded amounted to 26,111, with 8,141 killed. Little New Zealand took 7,571 casualties, with 2,431 dead.

The campaign was deemed by the Pommy Bastards in Chief to have been lost by the onset of winter, and the troops were evacuated in December. To have lost so much, and gained nothing at all gave the observance of the anniversary of the campaign a semi-religious air, and one with a distinct pacifist connotation. All the young men dead and maimed, all lost for nothing.

In 1922, the government was forced to declare a public holiday as people clamored for time off to honor the ANZAC. All the Diggers are gone now, and the holiday is much more secular. But it still features the unique Digger hat as the symbol, side folded up for Aussies, flat for Kiwis.

In Sydney, ANZAC Day has become both a commemoration and a bacchanal, just as Independence Day has here. They remember, though, because it was on the beaches below the cliffs at Gallipoli that the colonies became nations.

Sydney is a grand town, in youth or age. I don’t know if I will ever be back, but it is a hell of a place.

Copyright 2014 Vic Socotra

www.VicSocotra.Com

Twitter: @jayare303