The Field Marshal’s Daughter, A Life of Lies

Author’s Note: I have been wrestling with a treatment of the extraordinary career and legacy of departed Supreme Court Justice Ruth Bader Ginsberg. My sentiment about the Court has always been tempered by the adherence to the founding documents across centuries of change. Though not intended, the composition of the Bench has been a thing of politics all its existence, and has included temporary and lasting change. The current number of Justices dates only back 150 years, and was the product of a bitter fight, since the Framers did not mandate the composition of the bench, only the role of the Court in the triumvirate of power in the new Republic. I admired the Notorious RBG for her tenacity and trailblazing courage. I disliked her interpretation of the Constitution, but that was always tempered by her lasting and legitimate friendship with fellow Justice Antonin Scalia. There will be a large fight about her replacement in the next few weeks, so I will let the matter rest for now. The election, toxic as it was, now has even more excitement contained within its bounds. Should be fun. Coming to you over the next few days are pieces from Arrias, Marlow and Point Loma which I have enjoyed immensely and hope you do as well. Let the games begin.

– Vic

12 January 1984

The Field Marshal’s Daughter, A Life of Lies

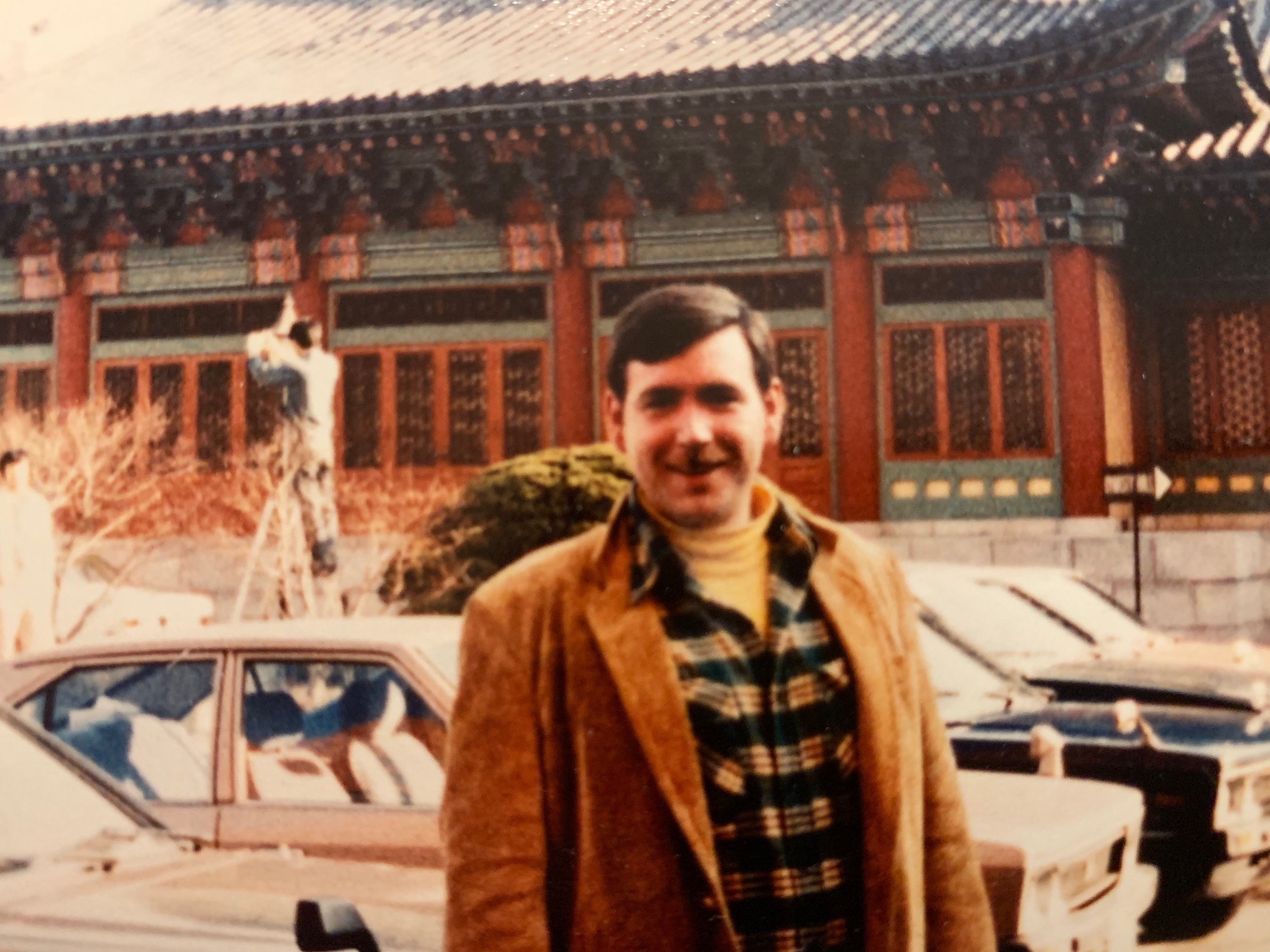

It was Tokyo, 1980. I was taking a break from the military coup in Korea. Major General Chon Tu Hwan, the most ambitious member of Korean Military Academy Class 11, had taken off his uniform, traded in his three stars for a crisp civilian suit and set up shop in the Blue House. One of his first acts was to brutally put down a student insurrection in a town called Kwang-Ju. I was tired from standing watch in the Indications Center, the focal point of the U.S. military presence in Seoul. I needed to go someplace that did not have a lot of guns on the street. I took a bus down to the air base at Osan and got a hop to Yokota to see some friends.

One of them was Jim the Spook. I had met him the first time at the seedy Adam Bar at the old Hamilton Hotel in the middle of Itaewon, the big shopping district near the Yongsan American garrison in Seoul. He spun some tales in his clipped English voice, Jim did, and how he came to be what he claimed to be was a puzzle. And his route and conduct in the uncertainties was still a new thing in our shared secret world.

I’m still not sure which level of him I understand. The craft of Intelligence is largely about peeling onions. Each layer has an access and a reality, related to but not necessarily true to the layer beneath. I was in the business and had met people from all our Agencies and a good number of theirs. We all have our quirks, our manners.

Military intelligence is pretty straightforward. Even when they are being discrete the players stick out. They are the storm-crows of crisis. Company spooks are credentialed as something else, and there is a sleek entitlement to them. The NSA guys tend to be anti-social, since they don’t have to talk to you to know what you are thinking. NRO Spooks are real secret, but they are doing you from space, so why would you care? NIMA is just looking at your picture, so take care of your hair. They can tell comb-overs. And all the rest of them, the drug spooks and the Justice spooks and the commerce spooks are the sideshow crowd. Mainstreamers don’t worry about them, unless you have branched off and are on the wrong side of the money.

Jim was an operational Army spook, or that was part of his legend. I was a much more garrulous person then, still a bit new to the world of lies.

I’ll give you the dossier as I heard it. He would be in his nineties now. Then, he allowed to 48 years of age. Whatever version of his life he shared his life was a ride on the roller-coaster of his times. It started with a hitch in the Coldstream Guards, and he claimed to service at Suez and in Kenya and Malaysia. Then to Korea, and then capture by the Chinese. Then to a camp in south China in chains. I did not stop him from telling me again. He seemed to know it pretty well.

“Quite right” said Jim in a clipped tone. “Then one day an NKVD Major showed up with the Chinese guards. The Senior Ranking Officer got us all together and told us we were for it unless we hit the wire that night. So, 17 of us went for it and 4 got across.

“You did what?” I said.

“Walked out of China. We didn’t know until we woke up one morning in a rice paddy and saw rifles leveled at us. I looked at the weapons and didn’t know what to think. They were British .303s. We thought the Chinks had grabbed a group of our guns. That was the first time I heard Thai.”

“Let me get this straight,” I said with wonder. “You had walked out of China and into Thailand?”

“Quite right. Surprised us, too. We thought we had crossed over into Laos someplace. We thought we forded the Mekong, but p’rhaps it had been the Kwai. Didn’t have anything in the way of maps, don’t you know.” He polished his glasses.

This trip, I was invited to his house at Camp Zama. His cover was Army Veterinary Corps, since they do all the food inspections for American units all over the Far East. It was a good cover for counter-intelligence, as he told it, though of course the reverse was equally true. He told me he was a Colonel when I looked at the sign by the door that read “Master Sergeant.” Cover issue, he said, and we had been talking about Ireland and the IRA as well, since that was his surname came from. Over drinks he took the opportunity to make a short biographical vignette of a German officer.

Albert Kesselring was the commander of German forces in Italy during World War II, and his daughter was Jim’s wife. She appeared with more drinks. She was a nondescript woman with brown hair and blue eyes as brilliant as Jim’s. She was introduced as Luisa, and told me a little about her father, his cheerful and intimate relations with the women of France between the wars. And of his efforts to save the great art of Italy during the savage campaign.

There was more, of course. Kesselring had service in both the Big Ones, and wound up as the man with the blue eyes who commanded Italy and the operational forces in North Africa. As the Wehrmacht Commander-in-Chief South, he was the overall German commander in the Mediterranean Theater. He was respected by the Yanks for his military accomplishments, but there were some broken eggs left after the omelette was complete

I did not comment on Monte Casino, the great monastery where he ran the aggressive defense against the Allied landing at Anzio, using the advantage of the high ground to slaughter thousands of Americans.

That aside, she seemed to think her father was a pretty good guy, and I realized that Jim did too. I ran some of the story over in my mind. Captured by Chinese. Irish by birth. Married to a Nazi’s daughter. Colonel masquerading as enlisted man. I turned the baton of a German Marshal over in my hands. Rich ebony wood, festooned with gold and capped with eagles and the insignia of the Reich. A real, no shit, Marshal’s baton. How the hell had she gotten it out of wherever it wound up?

I have to say it was the Marshall’s daughter that finally spooked me. Jim’s story was strange enough, but to look across the breakfast table at a very senior Nazi must have been intense. Her eyes were blue as a northern lake, and just as bottomless. Jim leaned over to me and suggested we go have some more drinks at a place the Japanese host service ran across town. I politely declined, and with much protestation of undying friendship, I finally got a cab and whizzed off in the soft darkness to Atsugi for other adventures.

It turned out to be a wise decision. I did some digging around when I wound up back in Korea. What I found took me into another layer of the onion, since it was all bullshit. Or at least that particular layer was. Back in 1910, Kesselring married a lady named Luise Anna Pauline (Liny) Keyssler, the daughter of a pharmacist from Bayreuth. The account I found stated plainly that the marriage was childless.

If that was true, then Jim’s wife was either delusional or playing some other game. There was a possibility, though strange and some of it located in open source material. In 1913, the year before the War, the Kesselrings adopted a boy named Rainer. He was the son of Albert’s second-cousin Kurt. I confess that the discovery left me bewildered. Further research indicated Kesselring was close to officers who had been involved in the assassination attempt against Hitler, the one conducted on 20 July 1944 by Claus von Stauffenberg. I had run across that one before entering the lair of secrets, and of the dozen or so attempts against the Fuhrer, it had a name. “Operation Valkyrie” was run inside the Wolf’s Lair field headquarters near Rastenburg in East Prussia.

None of the other attempts came to much, but this one was a last attempt to wrest political control of Germany and its armed forces from the Nazi Party and then make peace with the Western Allies before the Russians swept in from the east. They made a movie about it that I saw as a kid. The failure of the coup d’etat was spectacular, and led the Gestapo to arrest 7,000 assorted people. They executed 4,980. Piano wires were featured in many of them.

In my mind, it seemed possible that Kesselring’s son needed a way to stay low, and the woman with the blue eyes might have been somebody else entirely. That was enough of a string to follow up on, but by happenstance I discovered that a person claiming to actually be Rainer was appointed to a post by Helmut Kohl long after the war, and Jim’s spouse was not him. To a degree I was relieved, since I had a hard time imagining Jim doing…well, you know.

There would have been plenty of time for some hijinks to occur in a story this strange. After the war, Kesselring was sentenced to death for war crimes. The most spectacular of them was the murder of 335 Italian civilians in a massacre at a place called Ardeatine. There were others. In the aftermath, the sentence was commuted to life imprisonment, and a political and media campaign resulted in his release in 1952, ostensibly on health grounds. His heart gave out in 1960, twenty years before I met the daughter who did not exist.

I was working in Hawaii a year or two later when the another ill-fitting piece of the puzzle showed up. The rich wood of the Marshal’s baton still fascinated me. If she was not his daughter, was it just another fake? I had a pal who followed some of the leftovers from the conflict for personal profit. He told me over drinks down in Waikiki about something that had popped on the market. It was a Marshal’s baton, and it had belonged to Kesselring.

That was the story, anyway. It had been seized by an Army private who was serving as a scout with the 2nd Armored Division, the first US unit to enter Berlin. He had been ordered to search quarters used by high-ranking German officers, and found the baton. According to my pal, it remained in his possession until his death in 1977, when it passed to his widow, and then his son, who put it up for auction in 2010.

It was reportedly sold to a private bidder for $731,600. It was a curiously large price, since a priori estimates had ranged somewhere south of twenty grand. If Jim had gotten a piece of that, I would have expected him to go quiet.

I never saw him again, which is good from a career progression standpoint. It was also bad, because he had a great and complicated tale of life across our time and that of our fathers. He could have been nuts, but his wife seemed nice enough, and about that matter I had a couple questions to ask. And he actually paid for drinks.

Or somebody did.

Whatever he was, really, he had a hell of a story. And I have to say, it was a great introduction to the people and things I would deal with the rest of my professional life. In many respects, it was a life of lies. The Soviets called it “maskirovka,” or lies to cover actual capability and intent. It was an interesting life to lead. I thank Jim and the Field Marshal’s Daughter for a marvelous introduction in what was to come.

Copyright 2020 Vic Socotra

www.vicsocotra.com