The Last Hero of the Coral Sea

(ADM Noel Gayler in his office at Camp Smith, HI, 1976. An authentic hero and warrior, he was proud of being the first no-nucs officer to head the Pacific Command. Photo New York Times.)

It is appropriate to look back to the battle before the battle that changed everything in the Pacific.

I hope you saw RADM Paul Becker’s reminder the other morning. Now the 75th Anniversary is here, and I looked back through my archive of TAPS obituaries. This one called out to be remembered.

14 July 2011. ADM Noel Arthur Meredyth Gayler, 96, Alexandria, VA, of natural causes. He was the sixth Director of the National Security Agency (DIRNSA) at the height ot the Vietnam War, and followed a unique career path to four-star rank.

He began his service as a surface warrior- a Deck Officer of the time, like our pal and mentor Mac Showers. Noel became one of the highest –decorated fighter pilots in Navy history, and retired as the ninth CINCPAC from 1972 to 1976. His story-book career spanned 46 years of active duty and three wars, a unique wartime flight in a Japanese Zero fighter over the US Capitol, complete with the round red meatball of the Empire painted on the fuselage, and his position as the first anti-nuclear commander of CINCPAC, the military minister plenipotentiary for the United States at the zenith of its power in the Pacific basin.

Noel Arthur Meredyth Gayler was born in Birmingham, Ala., on Dec. 25, 1914, one of three children born Ernest and Anne Roberts Gayler. His father was a naval officer, who inspired him to enter the US Naval Academy in the class of ’35. His first assignment as an Ensign was in the Engineering Division on the battleship Maryland (BB-46). After an initial stint in the “Gun Club,” he transferred for his department head tours in the destroyer Maury (DD-401) followed by service as the Gunnery Officer on the destroyer Craven (DD-382).

Life as a “Tin Can” sailor paled for ENS Gayler, who saw that there was a new path to success in the service as the carrier air capability was ramped up in anticipation of war.

In March 1940, Gayler entered Flight Training at NAS Pensacola, the cradle of Naval Aviation. He was designated a Naval Aviator in November 1940, and was assigned to the Pacific in Fighter Squadron THREE (VF-3). He joined one of the most storied ready-rooms in Navy history. The “Felix the Cat” squadron was commanded by the legendary Jimmie Thatch, credited with inventing the “Thatch Weave” formation for air combat patrols, and who would later also go on to make four stars and command naval forces in Europe.

Another squadron mate was Medal of Honor recipient Edward “Butch” O’Hare. You have doubtless had a bad encounter in the Windy City airport named in his honor.

(VF-3 Squadron portrait. Noel Gayler is third from left in the first row, immediately next to Skipper Jimmie Thatch. Medal of Honor winner Butch O’Hare is sixth from left.)

VF-3’s “Fightin’ Felix” pilots were mentored by Thatch into a fighting machine that was prepared to take on the undefeated Japanese carrier force and it’s nimble fighters and demonstrate that the rugged Grumman fighter was in fact superior to the Mitsubishi Zero-sen aircraft when properly employed.

(Felix touched my life, too. Re-designated “VF-31,” the Felix squadron was part of Airwing SIX on our 1989 Cold War-ending Med cruise).

After Pearl Harbor the first important sea battle between American and Japanese forces was shaping up, and US Naval forces began to probe the perimeter of the massive new Japanese empire. Noel Gayler’s first Navy Cross was awarded after:

“…his ship was attacked by eighteen Japanese bombing planes on 20 February 1942. In the face of heavy antiaircraft fire, Lieutenant Gayler intercepted a formation of nine enemy aircraft and succeeded in shooting down one twin-engine bomber and a seaplane fighter, and aided in the destruction of two other twin-engine bombers, and bombed and strafed two enemy destroyers.”

In March of 1942, planes from the Enterprise had hit Japanese-occupied Wake Island, and Lexington (CV-2) teamed with Yorktown (CV-5) to strike enemy bases at Lae and Salamaua on the island of New Guinea.

Naval Intelligence was beginning to demonstrate significant contributions to the war against the Empire of the Sun. Intelligence derived from Station HYPO decrypts of JN-25 Naval Code indicated that the Japanese were planning to invade Port Moresby, near the eastern tip of New Guinea. The main body of the task force would sortie around this eastern tip, into the Coral Sea, and then attack.

Port Moresby was vital to Allied strategy, since if the Japanese established a presence there the strategic sea-lanes to Australia and New Zealand would be compromised. ADM Chester Nimitz made a bold role of the dice, ordering the bulk of his carrier force to engage. Lexington and Yorktown were ordered into the Coral Sea to intercept the Japanese battle force.

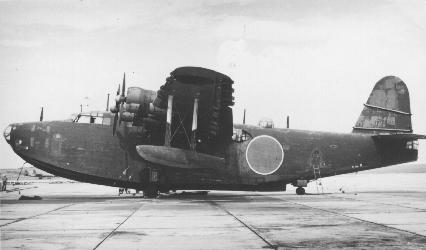

On the morning of May 5th, the two carriers heard a report from Lieutenant Commander James “Jimmie” Flatley, who led the Yorktown’s fighters. He was flying on Combat Air Patrol (CAP), and had spotted a Kawanishi flying boat spying on the task force.

“Where is he?” inquired Combat on Lexington.

“Wait a minute and I’ll show you,” radioed Flatley.

A fireball erupted in the clouds as his Wildcat gunned down the lumbering flying boat.

On its way down, the big plane almost struck LT Noel Gayler’s Grumman F4F Wildcat where he was orbiting near Lexington.

“Hey, Jimmy,” he yelled, “that one almost hit me.”

“That’ll teach you to fly underneath me when Japs are around,” Flatley quipped on the tactical frequency.

During the Air Battle of the Coral Sea three weeks later, Gayler’s aggressive courage earned him another Navy Cross, where with

“…utter disregard for his own life…he succeeded in destroying two enemy Japanese aircraft and in damaging two others.”

Three days later, he gained a third Navy Cross when on 10 March he intercepted and shot down an enemy seaplane fighter.

“In the face of heavy anti-aircraft fire he (then) conducted a vigorous and determined dive-bombing and strafing attack on two enemy destroyers, causing many personnel casualties.”

(IJN Kawanishi flying boat. Photo US Navy.)

In June 1942, on the eve of the Battle of Midway, Gayler was transferred to NAS Anacostia in Washington, DC. The U.S. Navy pulled its best combat pilots out of action to train newer pilots, while the Japanese kept their best pilots in combat. At NAS Anacostia he served as the Fighter (VF) Project Officer at BuAer From June 1943 to June 1944 to develop the improved Grumman fighter- the F6F Hellcat.

He had a stake in the new aircraft, since subsequently served as a test and evaluation pilot at NAS PAX River. He returned to combat as Commanding Officer of VF-12 from June 1944 to February 1945, and was Air Ops for the 2nd Carrier Task Force from March 1945 through the end of the Pacific War.

It was in his capacity as Task Force Air Ops that Gayler was able to commandeer an aircraft do conduct an aerial tour of Hiroshima. He was not the only interested tourist to visit- Chuck Sweeney, pilot of Bock’s Car, the B-29 that dropped the second atomic device on Nagasaki toured the city a few months after the peace. He took the other view, and for the rest of his life continued to believe the strike was the right thing to do, and that it had saved hundreds of thousands of lives.

Gayler did not see it that way. He flew over Hiroshima six days after the first atomic bomb was dropped on Aug. 6, 1945. “He was stunned; he saw nothing moving,” his widow Jeanne commented later. “It was imprinted on his mind, and he vowed to work to eliminate nuclear weapons.”

Gayler was present on the USS Missouri (BB-63) for the official surrender ceremony, and Operation MAGIC CARPET whisked him and millions of other servicemen home that November.

Jeanne Mallette Thompson Galyer’s recollection of Gayler’s memories of Hiroshima (Gayler’s first marriage ended in divorce) may contain a bit of historic revisionism, since despite his qualms about the horror of Hiroshima, Noel Gayler was destined to become the navy’s consummate nuclear warrior.

With the return to CONUS, he was assigned as Executive Officer and then Deputy Director of Special Devices Center on Long Island, NY, 46-48. The Center had been in the center of technology throughout the war, growing in prominence from a Section to a full-fledged Naval research center. It had explored technologies like television and innovative training devices for precision bombing and terrain modeling for aerial targeting.

The latter was a key element of Air Intelligence Targeting and was one of the key product lines of the CINCPACFLT intelligence division. In addition to the general knowledge of what Special Intelligence- the ability to accurately forecast enemy intentions to permit the bold strike- Gayler was attuned to the value of technology. Gayler’s Center was on the cutting edge of everything, and was also the home of the Navy’s first mainframe computer.

The command was also not far from the estate where Naval Intelligence exploited captured Nazi and Japanese technology, and there was frequent interaction. He also deployed from the Center to observe the third US atomic test series: Operation SANDSTONE, a three detonation series to test the effects of atomic weapons on surface ships.

(Operation SANDSTONE blast at Eniwetok Atoll, 1948. Official US Navy photo.)

In 1998, he commented to interviewer Steve Sapienza that: “I saw Hiroshima. Utter desolation. Not a thing moving. A little old dinky bomb did that. I participated in a second, I think it was, group of nuclear tests in the South Pacific, the Sandstone Series and I first saw what these things looked like, little thing from nineteen miles away is like the end of the earth. And I realized that the ideas about protection of ships — Navy — run away from the base surge, wash down of decontamination — all of that stuff was just nonsense. And I think — I think — by the way, something funny happened. Hard to believe you could be funny about nuclear testing, but we discovered that the sailors were kind of disappointed with us after all the work they’d done, washed down and whatnot, nothing much was happening until finally some character put a Geiger counter on the top of the cabinet [inaudible] and by golly, a passing sea gull had made a deposit there and it was radioactive. And everybody was happy.”

He managed to internalize his misgivings about the nature of his profession and was a consummate Navy leader in his combat and peacetime assignments afloat. These included duty in increasing levels of responsibility as Operations Officer in USS Bairoko (CVE 115) ‘48-49, CO of the deep draft USS Greenwich Bay (AVP 41) 56-57, Major command of USS Ranger (CVA 61) 59-60, and Flag command as Carrier Division (CARDIV) TWENTY, 62-63.

His shore assignments attuned him to technology, acquisition, politics and Human Intelligence operations, and the expose to the nature of how the Navy’s nuclear capability kept it at the heart of the strategic balance between the warring services.

Ashore, he headed the Fighter Design Branch in Washington, D.C., ‘49-51, and commanded VX-3 at Atlantic City, NJ, 51-54. In that job, he once flew from NAS Oceana east of Norfolk, Virginia, to Denver, Colorado and returned nonstop. The entire flight was flown below 200 feet in altitude to demonstrate feasibility of low-level penetration and attack. Gayler reported “Lots of astonished cattle” on his return.

He finally emerged from the cockpit to serve in the pressure-cooker OpNav Staff in the Pentagon, 54-56, He was Operations Officer for the Commander in Chief, Pacific Fleet, from February to June 1957, and then served as a Naval Aide to the Secretary of the Navy from June 1957 to April 1959. He was selected to be the U.S. Naval Attaché in London, England, from August 1960 to August 1962, a job that required regular intelligence reporting on events in the Court of St. James. He returned to the Pentagon late that year to become Assistant Chief of Naval Operations for Development.

Misgivings about weapons aside, his office was in the middle of the Submarine Launched Ballistic Missile program- in August 1967. He was Deputy Director of the Joint Strategic Target Planning Staff at Offutt AFB, Nebraska, from September 1967 to July 1969.

JSTPS was charged with planning Doomsday. It was the high-custodian of the Single Integrated Operation Plan, or “SIOP.” On a regular production cycle, the staff constructed the nuclear target deck for the manned bombers, submarine-launched and silo-based ICBM force.

In a 1976 interview after retirement, Gayler mused about his time there: “A very few persons go about the grim, necessary business of nuclear planning. Fewer still have seen a bomb tested: the light of a thousand suns, searing heat, immense shock, a wicked flickering afterglow manifesting in intense residual radiation. That’s a pity. We and the Soviet Union have tens of thousands of weapons. We better get them under control.”

From that position, ADM Gayler was nominated by President Nixon to become the 6th Director of the National Security Agency in July 1969. Nixon, urged by his National Security Advisor Henry Kissinger, to assign officers with broad operational experience- not intelligence professionals- in order to better control the intelligence community.

Gayler presided over the NSA SIGINT program, including clandestine and space-based reconnaissance, until Nixon nominated him to be chief of the U.S. Pacific Command (CINCPAC) in August 1972. In that capacity he managed the closing act of the Vietnam War.

In that post, the Admiral was in charge of all American armed forces in a 94-million-square-mile area from the west coasts of North and South America to the Indian Ocean. He was the American military adviser to the Southeast Asia Treaty Organization (SEATO). He was no opponent of conventional bombing, and oversaw the American air campaigns against North Vietnam and the secret bombing of Cambodia and Laos.

He retired from the Navy the year after Saigon fell to Communist forces, and in the same year wrote an Op-Ed article for The New York Times he was critical of the American nuclear posture, and increasingly too a position at variance with the official national strategy of massive retaliation.

His activism gained him notice as a military maverick. In 1986, he received an invitation from Jeanne Malette Thompson to join an organization she had founded (with activist Carl M. Marcy) called “The American Committee on East-West Accord.”

According to the mission statement, the organization intended to “promote rational relations with the Soviet Union and to work toward nuclear disarmament.”

The gravitas of the board that Admiral Gayler joined is unassailable. It included such Cold War giants as: Robert Strange McNamara, George F. Kennan and John Kenneth Galbraith, all of whom had crises of faith in the doctrine of containment and mutually assured destruction (MAD).

Soon after joining the board, he married Ms Thompson.

In December 2000, working with an organization called the Nuclear Age Peace Foundation, Admiral Gayler wrote a proposal for the elimination of all nuclear arms. “When a target country can be destroyed by a dozen weapons,” he wrote, “its own possession of thousands of weapons gains no security.”

He continued a vigorous campaign against nuclear weapons until shortly before his final illness.

He died peacefully at his home in Alexandria, Virginia, in 2011, the last and most prominent of the remaining heroes of the Coral Sea.

For all of them who were at the Coral Sea on this day, three quarters of a century ago.

With things nuclear so prominent these days, it might be worth thinking about the men who actually knew what it was all about.

Copyright 2017 Vic Socotra

www.vicsocotra.com