The Search for Wasp and Hornet

(This is the third part of the account of the search for two lost aircraft carriers from the war against Imperial Japan. These are the words of RDML Sam Cox, USN-Ret., director of the Navy’s History and Heritage Command. I consider his mission no less than sacred. – Vic)

I had been invited aboard the PETREL to participate in their search for two U.S. aircraft carriers lost in the campaign for Guadalcanal, the USS WASP (CV-7) and the USS HORNET (CV-8,) and, time permitting, other sunken U.S. and Japanese ships. To be frank, it would have been enough just for the opportunity to see Iron Bottom Sound, and pay my respects to those thousands of Sailors who left such a legacy of honor, courage and commitment that our Navy strives to live up to today. But, the chance to be the first to see aircraft carriers unseen for 77-years was an opportunity I couldn’t let pass.

The PETREL is a privately-funded, highly-sophisticated ocean research ship, equipped with state-of-the art autonomous and remote underwater research equipment capable of search of the ocean floor down to 19,000 feet, covering a larger search area, faster, than previous research ships.

It also had better internet connectivity via satellite than I have from my desk-top at work, which I suppose would be expected, given the ship was funded by Microsoft co-founder Paul Allen, who sadly passed away last year.

(Wreck of the INDIANAPOLIS, courtesy Paul Allen).

Mr. Allen did live to see his dream of finding the lost heavy cruiser USS INDIANAPOLIS (CA-35,) sunk with heavy loss of life in the last weeks of WWII; the PETREL continues to fulfill his wish of honoring his father’s WWII naval service by locating other U.S. ships lost in action.

The U.S. Naval History and Heritage Command’s (NHHC) Underwater Archaeology Branch pays close attention to any effort to find sunken U.S. Navy vessels. Under customary international maritime law, sunken naval vessels remain sovereign property, and the “right of salvage” or the “right of finds” for sunken merchant ships or commercial vessels do not apply.

The U.S. Navy retains title to all sunken ships and aircraft wrecks (including terrestrial) in perpetuity unless specifically legally divested (the Civil War ironclad USS MONITOR sunk off Cape Hattaras in 1863 is a rare example.)

In addition, the U.S. Navy has traditionally viewed a sunken naval vessel as a “fit and final resting place,” for U.S. Navy Sailors lost at sea due to the enemy or the elements, and this has recently been codified by U.S. Navy Regulation (at NHHC’s instigation.)

Many of these wrecks are “war graves,” or otherwise represent the last resting place of Sailors who gave their lives in the service of our country, and as such deserve to be treated with the utmost respect and decorum; they are literally hallowed sites as much as the Tomb of the Unknown Soldier or Arlington National Cemetery. In addition, many of these sunken craft are hazardous due to unexploded ordnance or risk environmental contamination due to trapped fuel oil, as well as other potential dangers.

In 2004, the “customary” maritime law was legally codified by the U.S. Congress under the “Sunken Military Craft Act (SMCA),” for U.S. warships, naval auxiliaries, or other shipping operating under U.S. government control in non-commercial service (e.g., merchant ships carrying U.S. war material in convoy) as well as military aircraft. The act applies to U.S. ships that meet the definition of “military craft” anywhere in the world, but applies only to U.S. citizens.

That is, U.S. sunken military craft outside U.S. territorial waters are not protected by the SMCA from salvage activity by foreign entities, although “customary” maritime law still applies to the extent that the foreign entity chooses to respect it.

Nation-states generally do respect customary maritime law (which was also codified under the United Nations Law of the Sea Convention, although the U.S. signed but has not ratified it.) However, some salvagers conduct operations either unbeknownst to nations or outside any national jurisdiction.

For example, within the last several years, British and Dutch warship wrecks lost during the Battle of the Java Sea in February 1942, such as the British heavy cruiser HMS EXETER, have been blown apart by explosives and the pieces brought up by claw crane to barges (most likely from China,) with human remains buried in unmarked mass graves ashore, and the remains of the ship itself used as scrap (metal from shipwrecks that occurred before the advent of atmospheric nuclear explosions appears to have a market value worth the effort.)

In the case of the Java Sea, such salvage operations are believed to have been conducted without the knowledge of official Indonesian government authorities.

The U.S. has lost two ships to this illicit activity in the Java Sea, the destroyer USS POPE (DD-225) and the submarine USS PERCH (SS-176,) with the saving grace being that neither vessel went down with their crews (their hell began in Japanese prisoner of war camps.) NHHC continues to work closely with the U.S. Country Team in Jakarta to have Indonesia declare the wreck of the heavy cruiser USS HOUSTON (CA-30) a protected maritime conservation zone so that she does not meet the same fate.

HOUSTON was lost on 1 Mar 1942, along with the Australian light cruiser HMAS PERTH in a heroic night action against an overwhelming Japanese force in the Sunda Strait; approximately 600 of her crew went down with the HOUSTON and are likely entombed within. Many others died in the water or in Japanese captivity.

Throughout all previous incarnations of the command, NHHC has kept a data base of known or estimated positions of sunken U.S. naval vessels or aircraft as a matter of course and for the sake of history, which includes about 3,000 shipwrecks of all sizes dating to the Continental Navy plus 14,000 (and counting) aircraft wrecks.

This data base activity now has additional impetus as NHHC is the U.S. Navy’s executive agent for administering SMCA, and there are severe civil penalties (up to $100,000 per day) that can be levied on any U.S. citizen that deliberately disturbs a wreck covered by SMCA.

In order to prove any such case in court, however, it is important to know the exact location and condition of wrecks in order to prove disturbance. Although Indonesia came under criticism for failing to protect the Java Sea wrecks, the reality is that even the U.S. Navy lacks the resources to monitor the condition of most of sunken naval vessels.

Working with legitimate private researchers such as the PETREL, or receiving reports from responsible recreational divers, is generally the only way NHHC can learn of the location and condition or ongoing disturbance of U.S. Navy wrecks.

Under SMCA it is perfectly legal for anyone to dive on a U.S. Navy wreck anywhere in the world (consistent with local laws) so long as there is no intent to disturb the wreck. If there is a valid scientific, educational, archaeological, environmental or other U.S. Government purpose, NHHC has authority to issue a permit to a requestor for controlled disturbance of a wreck, which so far has been extremely rare. (Special policies are in place in the case of supporting activity by the Defense POW/MIA Accountability Agency (DPAA.))

Initially, Mr. Allen’s group (operating under his corporation, Vulcan, Inc.) began hunting shipwrecks in 2015 using his private yacht, OCTOPUS (which was equipped with very sophisticated underwater search gear,) and relying entirely on their own independent research.

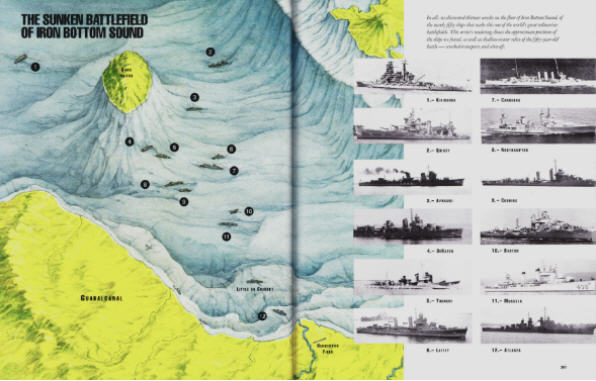

OCTOPUS’s survey of U.S. and Japanese ships in Iron Bottom Sound and the location of the Japanese super-battleship MUSASHI in the Philippines attracted NHHC attention.

It quickly became apparent that Vulcan’s Subsea Team was a very responsible organization, with exceptional capability, that treated the wrecks with the utmost respect, with no intent other than to find the wrecks and then publicize the courage and sacrifice of those U.S. Sailors who served aboard (and had the wherewithal to get these stories of U.S. Navy valor into widely disseminated media, such as the New York Times and CBS (and not just an H-gram from my office.)

In addition, Vulcan’s Subsea Team voluntarily shared positional and condition information (including extensive video and photos) with NHHC, and made clear they had no intent to publicize the precise coordinates of the wrecks. This began a collaborative relationship between Vulcan and NHHC, at no cost to the U.S. Navy other than staff time I chose to commit to the effort (which is a sunk cost.) I would also note that NHHC collaborates with a few other research entities, such as Bob Ballard, so long as the research is legitimate, there is no intent to disturb the wreck, and the exact location is not publicized.

With the purchase of the PETREL in 2016, and the desire by Mr. Allen to find the wreck of the USS INDIANAPOLIS (after multiple previous efforts by others had failed,) PETREL’s underwater search group approached NHHC for additional data to supplement the considerable amount of data they had already amassed.

As Director of NHHC, I had previously directed NHHC historians and underwater archaeologists to do a “deep dive” (in the records) regarding the loss of INDIANAPOLIS. As a result of that, along with modern wind/current drift computer modeling courtesy of the U.S. Naval Academy Oceanography Department, NHHC determined that the actual position of INDIANAPOLIS’ loss was about 40 NM west-southwest of the “official” U.S. Navy position used in the Court of Inquiry and court martial of Captain Charles McVay in 1945.

I directed this information be shared with PETREL. Given PETREL’s exceptional capability, she would have eventually found INDIANAPOLIS without NHHC’s help, and in fact the actual position of INDIANAPOLIS was about the same distance west but a bit further to the north than NHHC’s estimated position (but a lot closer than the “official” Navy position.)

Nevertheless, the successful search of the INDIANAPOLIS, and Vulcan’s care in managing the release of information (enabling NHHC to initiate contact with the INDIANAPOLIS Survivor’s Association, so that the remaining few survivors learned of the discovery before it hit the media,) and the no-cost sharing of data from PETREL established a solid foundation for a trusted relationship that continues to this day.

The Vulcan Group prefers to keep future operations by the PETREL as proprietary information and does not divulge positional data of the ship while underway. However, since the INDIANAPOLIS search, PETREL has shared future plans with NHHC.

During 2018, PETREL located the aircraft carrier USS LEXINGTON (CV-2,) lost during the Battle of the Coral Sea in May 1942, the anti-aircraft light cruiser USS JUNEAU (CL-52,) sunk by Japanese submarine I-26 after being severely damaged in the 13 November 1942 battle off Guadalcanal, and the light cruiser USS HELENA (CL-50,) sunk during the Battle of Kula Gulf in July 1943. The 2018 Expedition searched for, but was unable to locate the destroyer USS STRONG (DD-467,) sunk in the southern Kula Gulf by what is believed to be the longest successful torpedo shot in history (11 NM) by a Japanese Type-93 “Long Lance” torpedo. PETREL would subsequently locate STRONG on 26 February 2019.

Tomorrow, we will embark on RV Krestrel, and hunt for the graves below Iron Bottom Sound.

Copyright 2019 Sam Cox

www.vicsocotra.com