The Third of June

Editor’s Note: I am a little frustrated. I was supposed to be in Honolulu this morning. But that does not change the significance of the date, 75years ago. We talked about some of this yesterday, as the epic Battle of Midway was nearing. The 3rd of June was a special day, and we ought to remember it. It was when the geography of the Pacifc began to change for the better part of a century. This account of that day (and others) is from a speech written and delivered by former Director of Naval Intelligence (and later DIA) Jake Jacoby in 2012. He delivered it with Mac Showers on the stage, on his last trip to the lovely isles:

“Good evening, all.

With all of the discussions about the historical ties to the events of 70 years ago, I thought I’d take a different approach and talk about one of the most interesting days of my Navy career.

The date was June 1995 and I was a frocked RDML and serving as the J-2 at CINCPAC. As an old guy who’s no longer on active duty and not bound by the changes in names and propriety over the past number of years, I’m going to continue to refer to the command up the hill as CINCPAC and the leader of that command as The CINC through the rest of my remarks.

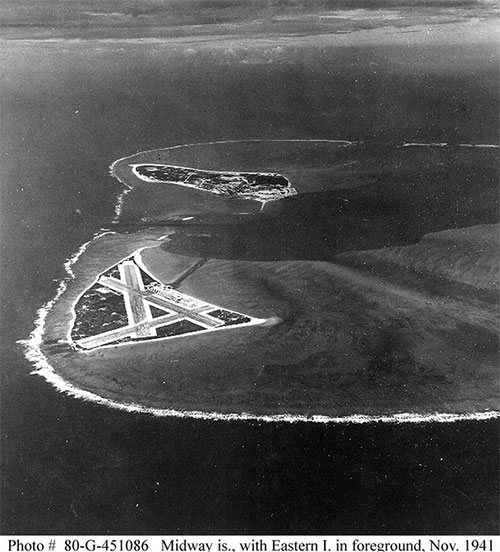

It may be a surprise to many of you that as the J-2 on that senior staff and as one of the duty roster Flags, you were called upon for duty as assigned, meaning that when it was your turn, you got the opportunity to represent the CINC at various events. (I don’t want to cause any dismay in this regard, but these opportunities don’t end when you make Lieutenant JG or First Lieutenant.) So, as the dutiful staff officer, and despite the fact that I had plenty of other things to do, I reported to the flight line to board the CINC’s P-3 at oh-dark-thirty for a flight from Hawaii to Midway Island to represent the CINC at the dedication of a monument commemorating the Battle of Midway. As is the case with most junior Flag’s, I was fully equipped with a briefcase full of all of the work that would have dominated a normal working day and set about to make the most of the plane ride.

It was interesting to note that the last two passengers to board the CINC’s P-3 prior to departure were two civilians of an indeterminate age….meaning that they were considerably older than I was and were clearly the oldest on the aircraft. But, paying that no mind, I buried myself in the briefcase and we proceeded to Midway Island.

After arriving at Midway, we were taken on the grand tour by a National Parks Ranger, which lasted about 30 minutes, and then we were sequestered in an old hanger awaiting the ceremony which was to begin about two hours later. I found myself whiling away that time in the company of the two older passengers from the flight from Hawaii. After approaching them and introducing myself, I asked their names and their association with the events of the day. They introduced themselves as Jack Reid and Bob Swan, the pilot and navigator of the PBY Catalina sea plane from VP-44 that first sighted and reported the location of the Japanese fleet on June 3, 1942 as the Japanese approached Midway Island.

Being nosy by nature and an Air Intelligence Officer by training, I proceeded to do the equivalent of mission debrief 53 years after the fact. According to the two aviators who were both Ensigns at the time, they took off from Midway that morning with instructions to fly a compass heading out 600 NM to a pre-determined orbit point and then to set up their surveillance orbit. However, due to more favorable winds than briefed (again, it is the fault of the Weather Guesser), they arrived on station with more flight time and fuel than anticipated. So, they made the decision to press on 50 miles past their designated orbit point.

(Now this is in direct contradiction to the other published accounts by CAPT Jack Reid, USN (Ret) that claimed that his crew chief was a superstitious sort who routinely loaded three 50 gal fuel drums in the aircraft to ensure that they had sufficient fuel and that the additional fuel permitted them to proceed past the designated loiter point. For me, I don’t care because the outcome is the same….they pressed on. For those in the audience with experience debriefing aviators, I’d say there is little likelihood that they would have revealed the truth concerning carrying unauthorized fuel to an AI on debrief, regardless of how many years had passed at this point. I guess they thought it still might get into a published debrief.)

Jack Reid continued with most of the commentary, with Bob Swan saying little. Jack said that upon sighting the Japanese fleet, they radioed back on the sighting and location and then they spent approximately two hours on orbit ducking below the visual horizon to pop up occasionally to verify the status and location of the enemy and to avoid detection, and near-certain engagement by Zero’s, before departing station for a return to Midway. The force Jack’s crew had sighted consisted of 17 ships, battleships, cruisers, destroyers and transports headed for Midway.

I might add that their return flight is not as simple as it might sound, because there were no navigation aids broadcasting for an aircraft that had been flying a compass heading and orbiting for hours and was then required to return to base using a dead reckoning solution.

At this point, I believe I need to slow down for a moment for the younger members of the audience, meaning RDML Becker, CAPT Loveless, CAPT Fannell or anyone younger than RADM Showers or VADM McConnell, to help them keep up with the story by explaining that in the pre-GPS era there was something called a High Frequency beacon system that when turned on, permitted a flight crew to dial in that beacon and to fly to that beacon and find their way back to home base. However, when turned off, they basically were on their own. Guess which configuration the beacon system was in on June 3, 1942.

While not part of my debrief, but for historical context, the following day, Jack Reid and his co-pilot flew more than 14 hours, again providing important contact reports. His PBY Catalina was attacked by Zeros and anti-aircraft guns on a Japanese cruiser, but Jack got his aircraft and crew safely into the clouds. When he landed in one of the lagoons at Midway, one of his engines died due to lack of fuel. The following day, he was airborne searching for lost pilots and crews.

Anyway, back to my story, our intrepid aviators became American heroes. Or, at least Jack Reid did. However, the story doesn’t end here. First, I suspect that Mac Showers and his compatriots had a lot to do with providing the vector for that aircraft on June 3 and had a pretty good idea of where the most lucrative area was for search and surveillance, unbeknownst to that aircrew who thought they had the good fortune of the right vector and an additional 50 miles of surveillance range. While there was a certain amount of luck involved, it was luck layered on top of great cryptography.

At one point in the debrief, pilot Jack Reid was called away and I continued my discussion with Bob Swan, the co-pilot. I asked him how things turned out for them following the battle. He said that Jack became an American hero and spent the rest of the War selling War Bonds back in the States while Bob spent the rest of the war flying sea planes from various little atolls in the Western Pacific. So much for the glory of being Number 2.

Bob had some great stories to tell, for example, I asked about the world of no NAVAIDS (GPS for the younger audience) and he said that it got hairy sometimes. He recounted a situation where a squadron-mate got lost and ran out of fuel and had to put the seaplane down in the ocean. I asked what happened next and Bob said that the pilot ignored all regulations and came up on the radio passing best knowledge of his location and transmitting a beacon in obvious disregard for all OPSEC guidance. Bob said that the crew figured that they were lost and any Japanese who were monitoring the frequency and trying to locate them would also be lost, so it was OK. If the Japanese came after them, they figured things would not be much worse than the predicament they were already in…floating in the Pacific in a sea plane that was out of gas.

The next morning, Bob and his crew were dispatched with an aircraft full of 50-gallon drums of aviation fuel to find the downed aircraft. Then, an air crewman from Bob’s aircraft jumped wingtip-to-wingtip to pull a garden hose from Bob’s aircraft to the out-of-fuel aircraft to siphon gasoline from those drums for hours and to enable that aircraft to follow Bob back to base.

By the way, Jack Reid stayed in the Navy and retired with more than 30 years of service as a Captain. Bob Swan stayed in the Reserve and retired as a Commander.

With this great appreciation for the lot of PBY pilots and crew, I took my seat in the front row for the Battle of Midway National Memorial ceremony, but my day was not complete.

(USN P-3C Orion)

Upon boarding the P-3 for the flight to Hawaii, we were informed that we would be flying to the location of the battle, before returning to Hawaii. Since I was but a passenger, I settled back into the seat, but found it intriguing that the Senior Chief who was the Plane Captain was rigging what appeared to be a harness near the P-3’s hatch and then I felt the P-3 throttle back and descend in the twilight to a low altitude. I have to say that the entire evolution that followed appeared to be more makeshift than practiced or conducted by some set of NAVAIR regulations.

(ENS George Gay, USN)

The Senior Chief then proceeded to open the hatch and to toss a wreath into the ocean, followed by opening a wooden box and scattering the contents of that box into the skies above the battle area. As the Senior Chief prepared for the scattering of the contents of the box, the pilot keyed the internal intercom and asked us all to be at attention in our seats for the burial at sea of the remains of Ensign George Gay who was the pilot shot down in the early waves of aircraft prosecuting the Battle of Midway, was in the sea for the duration of the battle and was credited with documenting the Japanese losses during the battle. Ensign Gay died of a heart attack in Marietta, Georgia on October 21, 1994 and asked that his ashes be scattered at the battle site.

Now let me circle back from that momentous day and ask a couple of questions that have nagged me for many decades. So, what’s the visual horizon of a person in the water in the middle of a wide-ranging naval battle? How could one observer with that visual horizon document all of the Japanese losses over the protracted battle? Would he have been able to have read and then committed to memory the names of the ships that were lost? Or, might it have been that cryptologists in Hawaii had ground truth from Japanese reports and needed an unclassified source to put that information out to the American public and the world as the tide of war in the Pacific turned against the Japanese just six months after the stunning surprises of December 7, 1941?

Heck, I don’t know. You might have to ask Admiral Showers and he may not choose to answer the question, even these 70 years later.

Addendum: I was followed by RADM Showers who made note of my questions and proceeded to answer them during his remarks. He said that the cryptologists did not provide information on what vectors to fly from Midway and that Jack Reid and crew did it all on their own. He also said that, “Ensign Gay had a vivid imagination and concluded that the three carriers had been sunk, probably because he was able to see smoke from three major fires burning simultaneously.” I’d note that RADM Showers did not intimate that anyone from his unit did anything to discourage Ensign Gay from reporting his “eye witness” account.

Copyright 2012 Jake Jacoby

www.vicsocotra.com