The War in the West

Patrick Griffin: The Adventure of a Lifetime

By Rebecca Blackwell Drake

(Author Becky Drake, speaking to a gathering of Civil War enthusiasts on the Hill of Death at Champion Hill. That struggle was part of the Union campaign that built the reputation of U. S, Grant, and was part of the strategic effort to secure Vicksburg, the Gibraltar of the South. The city dominates the bluff above the Mississippi River and was the lifeblood of the Western Theater. Grandfather James was there during the siege, and in the first year of his three-year enlistment participated in the massive engagement at Shiloh, also known as Pittsburg Landing in the south. The War still casts long shadows here in The West).

Author’s note: This narrative is based on an interview with Vic Socotra, great-great nephew of Patrick Griffin. Genealogical information was compiled by Barbara Foley Nakaska in 1963. She was Patrick’s great-niece, and heard the stories first hand from their source.

Patrick Martin Griffin, one of the most colorful figures to have fought in the Battle of Raymond, MS, was born on St. Patrick’s Day, 1844, in County Galway, Ireland. Not only was Patrick named for the patron saint of Ireland but he was also blessed with the gift of blarney, an Irish term meaning the gift of gab. During his long lifetime, Patrick used his uniquely Irish gift to his advantage, and his tales still stir the blood today.

Patrick immigrated to the United States around 1847 with his parents Michael and Honora Griffin. The Potato Famine was at its height, and in desperation, the little family left three children behind to travel to the New World. Patrick was only three years old when the sailing ship David completed an arduous thirteen-week passage of the Atlantic and docked at the bustling port of Baltimore. Michael found employment as a navvie, laying track for the B & O and L & N Railroads, and followed construction south from Maryland to the Potomac river port at Alexandria, Virginia. Two years later, the family followed the rails to the new transportation hub at Gordonsville, VA, and thence west to Nashville, where Michael continued to swing a hammer for the railroad.

The Griffin family had just begun to live the American Dream when hard manual labor took its toll. Michael died of sunstroke on the job, leaving Honora a widow with a young son to raise. Instead of returning to her family in Ireland, she decided to make Nashville her home and eventually remarried. As a young teenager, Patrick began to hang around local Irish pubs and became captivated with the Sons of Erin, a company of Irish lads who loved military drills, music, whiskey and the Democratic Party.

Too young to hoist a rifle, Patrick beat the drum as the lads marched in the park.

In 1861, with the rumblings of war on the horizon, Patrick begged his mother to let him enlist in the Sons of Erin commanded by Randal McGavock, a leading figure in Nashville society and former Mayor. He was a dashing graduate of the Harvard Law School, and had been elected to office in 1858. He had ambitions far beyond the city on the river, though his prospects were dimmed by the rise of the Republicans, and decided to cast his lot with the Secessionists. The Sons of Erin flocked to his side, and Patrick was no exception.

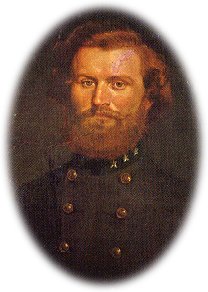

(Young Uncle Patrick as a combat veteran, having returned from prison in Chicago in 1862.)

Honora argued that Patrick was too young to enlist, but the teenager would not be deterred from his desire to go to war behind the charismatic Lt. Colonel McGavock. In April 1861, with the Sons of Erin flag flying high, Patrick and the other Irish volunteers left Nashville by boat to join the Confederate Cause.

(Grant couldn’t make a go of business after the Mexican War, but he was a hell of a combat commander. His rise to fame and the great rivalry with Robert E. Lee was based on his success in the War in the West).

His fascination with war soon lost its charm when the Confederate army, including the Sons of Erin, was captured at the Battle of Fort Donelson by the forces of a hard-drinking, cigar-puffing veteran of the Mexican War named Ulysses Simpson Grant. The regiment was sent to a prison in Chicago where they “wintered it” while waiting for prisoner exchange. In September 1862, after seven months of confinement, Patrick and the other prisoners were exchanged and left for Jackson, Mississippi, for the reorganization of 10th Tennessee.

A year later, May 12, 1863, Patrick was captured once again, this time during the Battle of Raymond. The days in Raymond were the most memorable in a life of adventure, and the saddest. Colonel McGavock, his father-figure and commander, was killed during the final stage of the battle.

In his memoirs, Patrick recalled the death: “We had marched up on a rise and were out in the open, and they were in the woods about one hundred yards in our front when they began to fire on us….We had been under fire about twenty minutes, when I heard a ball strike something behind me. I have a dim remembrance of calling to God. It was my Colonel. He was about to fall. I caught him and eased him down with his head in the shadow of a little bush. I knew he was going, and asked him if he had any message for his mother. His answer was ‘Griffin, take care of me! Griffin, take care of me!’ I put my canteen to his lips but he was not conscious. He was shot through the left breast, and did not live more than five minutes.”

Patrick also recalled how he took McGavock’s white linen handkerchief from his left hip pocket and dipped it in McGavock’s blood. He would give the handkerchief to Louisa McGavock, the colonel’s mother. Patrick also collected his colonel’s personal effects: a signet ring, gold watch, and a few papers; among them was McGavock’s journal, with its poignant last entry that morning.

The Confederates were overwhelmed and Patrick was again captured by the Yankees. The day after the Battle of Raymond, Patrick was issued a parole to bury his Colonel in the Raymond cemetery. A wooden coffin was hastily nailed together and laid tenderly on a bed of a hired wagon for transport to the local cemetery. Trailing along behind the casket was a ragged squad of Confederate prisoners and a small gathering of townspeople.

Vic Socotra, great-great nephew of Patrick Griffin, commented on Patrick’s memoirs of the Battle of Raymond: “I had a chance to review Patrick’s service record at the National Archives a few years ago, and his story appears based on fact, regardless of the filigree that grew around it as the years went by. The story of his interaction with Colonel McGavock’s body at Raymond is there, in the spidery handwriting and brown ink of the time. If the story got better with time, that is only to be expected.”

Following the Battle of Raymond and a miraculous escape from the Yankee captors, Patrick continued his service in the war. After the fall of Atlanta, he was detailed to be one of General Hood’s scouts. A biographical sketch of Patrick Griffin written in 1902 states, “He was wounded twice, and was one of three surviving members of the company after the battle of Peachtree Creek. After the fall of Atlanta, he was detailed to General Hood’s Headquarters Scouts. In sum, he was captured three times: after Ft. Donelson, after the slaughter in Raymond, and at the end of the war when Hood turned himself in. Exchanged, escaped, and paroled were the terms he used as he accounted his returns. Along the way, he participated in twenty-four general engagements.”

After the war, Patrick, age 21, returned to Nashville and began a civilian life. He married Bridget Welch and had six children with her, though only three survived infancy. They named one of the girls was named Louisa McGavock in memory of Colonel McGavock’s mother, Louisa McGavock. After Bridget’s death, he married Annie Dean Breene and had two more children, both sons. Patrick’s career was linked to the Nashville, Chattanooga & St. Louis Railroad in Nashville, where he worked for 52 years.

He built a fine home and became Superintendent of the Planing Mill for the NC & SL.

In 1905, Patrick’s “gift of gab” led him to submit a lengthy and delightful article to the Confederate Veteran Magazine in which he reminisced his war experiences. The stories he recreated were colorful and essentially truthful – although most likely with a certain amount of filigree brought about through the passing of time.

Patrick’s gift for words and story telling has been passed down to his great-great- nephew, Vic, an itinerant intelligence officer and radio correspondent. Of his Irish ancestors, Vic wrote: “I was going to leave St. Patrick’s Day behind this year, but it appears that the Irish are not done with me just yet. I got an e-mail from Nashville, asking for some information about my ancestor who appears in a portrait commissioned for the history of the Irish regiment raised in that city to fight for the Confederacy.

I have seen a copy of the painting, and it is an impressive thing, with a big gray horse rearing and a proud green banner floating. What I would really like to see is a family portrait of the dashing young Confederate, his lovely Irish sister (Barbara) and her husband, a strapping young Yankee teamster. But that is the root of the story, young people in a wild new land who were swept away in allegiances to new states and new causes. As for great-great Uncle Patrick, he is much more of a rogue than I had even expected – or – maybe he was just a 17-year-old Irish kid off to the greatest adventure of a lifetime.”

Patrick Griffin lived through America’s hardest years as a nation in the War Between the States, and saw his son Walker march off to the War with Spain. He then saw World War One come and go, and on June 5th, 1921, the proud old Confederate soldier died at the age of seventy-seven, in the house he built with his own hands.

His daughter Louisa McGavock Griffin, named for the mother of his beloved Colonel, lived in the house for another thirty years.”

_________________

Postscript: The gift of the Blarney ran in the family. After the Griffins settled in Nashville, Patrick’s sister, Barbara Griffin, immigrated to America. In 1864, she caught the eye of Irishman James Foley, who was regimental teamster in the 72nd Ohio Volunteer Infantry. He had survived Shiloh and Vicksburg, but Barbara was irresistible. They married while he was on furlough, and his new Irish bride used her “silver tongue” to persuade James to desert, rather than return to the fighting. They too lived long lives after the great war, and kept in touch with Patrick and his family down through the years.

And there-in, gentle readers, lies the story I will attempt to tell. It is much better than dealing with the present.

Copyright Vic Socotra and Rebecca Blackwell Drake 2015

www.vicsocotra.com

Twitter: @jayare303