Thirteen Years

I wrote the date and then I had to stop. Thirteen years, almost to the tick of the clock. I watched the President last night, and I know only one thing: we are not safer today than we were then, and this is a mess. Despite all the blood and treasure we have spent since The Day, we have not made it so.

I have notes in my work journals from that summer a baker’s dozen years ago. There was a sense of dread abroad in the land for those of us who had to think about; there were things that had happened that made another awful incident inevitable.

There was enough already to be uncomfortable about. The Embassy bombings in East Africa- I had a pal who was in the basement of the one in Nairobi when the truck bomb went off. The World Trade Center garage bombing. The USS Cole attack. All the way back to the Beirut Embassy bombing, where my shipmate Wheels was killed.

I took it all a little personally, but nothing like what I was going to be feeling on that beautiful September day.

I had stopped by the office of the Director for Plans on the Intelligence Community Staff one day not long after I left the Pentagon to work at Langley, and plopped down on the chair across from Deborah’s desk. Her windows looked out of the Original Headquarters Building on the sixth floor over the trees.

Langley is a pretty campus, very pastoral.

“You know they are going to smack us, right?” She nodded. We all knew something was coming. I have the notes: “Tel Aviv, New York? What’s next?” reads one note from July of 2001.

On that particular morning, I happened to be staying in the Walter Reed BOQ on Fort Leslie J. McNair in SW DC. It is an old brick structure, built to the standard plan of the 1880s Army. It was a drafty building with small rooms and doors that did not quite fit the frames anymore.

In keeping with the pre-air-conditioned era in which it was built, each floor featured a broad veranda accessible from the central hallway. There was a splendid view of the Potomac from the east, and the vast low sandstone bulk of the Pentagon across the river.

The Community Management Staff does not rise early, and I could have adjusted my hours later. Old habits die hard, though, and I was up at five on that Tuesday morning to shower and shrug on my tropical whites with the four gold stripes on the shoulder-boards, full ribbons and the identification badge of the Joint Chiefs of Staff below.

I could have worn civvies; CMS was not much of a stickler for military precision, and living with the Agency we did, was more than accustomed to people not being exactly who they pretended to be. Plus, traveling light as I was at the time, not having to worry about a full wardrobe was a convenience.

I walked down to the car, to head for the office just like the assholes who were about to change our world. I put the top down on the car; it was beautiful in the pre-dawn. The inky sky was illuminated by a elegant silvery moon, no clouds. The temperature was perfect.

I drove out Maine Avenue to catch the 14th Street Bridge and cross over into Virginia. The campus at Langley is best accessed by the George Washington Parkway, and the spaghetti of roads around the Pentagon is confusing enough even for the veteran DC driver.

I took the Pentagon exit, since I knew that way to the Parkway better than any other from the eight years I worked there. I drove up Boundary Channel Drive, past the River Entrance to the Building. Lady Bird Johnson Park is to the east, across the little stream that is actually the boundary between the District and Virginia.

The great mass of the Pentagon was lit by moonlight, and just starting to come awake with the business of Defense. I passed the wide swath of the North Parking’s sprawling asphalt, and then arced onto Route 27 to hook up to the Parkway.

All I recall, smoothly passing under the leafy limited-access road was the pleasant quality of the air against my skin. There was nothing remarkable about the exit onto Dolly Madison to approach the campus from the east.

The passage through the gate on to the campus was uneventful; the black-clad guards were mostly recruited out of Marine Embassy Guard detachments overseas and were crisp and professional.

I got a decent parking place, a perk of arriving early, and badged in and took the elevator up to the office suite on the sixth floor. I forget whether I had to unlock the vault; normally I did, being one of the first ones in.

That would have been about the time that assholes Mohammed Atta and Abdulaziz al-Omari passed through security at Portland International Jetport in Maine to connect to Los Angeles-bound American Airlines Flight 11 at Logan in Beantown.

I did not have a window in the suite on the 6th floor, but did have my own office, so I did not see how pretty the light was coming up on the trees outside as Marty and Rock arrived in their shared space across the passageway to continue the agonizing process of coordinating a DCI-level directive through the fractious and uncooperative interagency with other members of the Community.

Seventeen other assholes cleared security checks at Logan Airport, Newark International Airport, and Washington Dulles Airport as we got ready for a day of bureaucratic process. Even though some of the assholes aroused suspicion at security screening, none were prevented from boarding their flights.

We were talking about some nuance in one of the paragraphs in our document in our morning huddle that started at 0830 sharp. We were already well into it when Steph came down the hall, announcing to all within earshot that an airplane had hit one of the towers of the Trade Center.

“Jesus,” I said. “Remember, though, this has happened before. A B-25 bomber flew into the Empire State Building during the war.”

Marty and Rock looked dubious, and the conversation about the objections that Fort Meade had to our document was suspended. News of the second crash was in real time, what with attention glued to CNN in the offices that had televisions.

“That’s it,” I said and shut my notebook. “We are under attack. You guys get out of here and get home.” They were both retired officers, contractors now, and they left with alacrity, to spend the next several hours in their cars in the mess of the entire Federal Government attempting to flee.

I went back to my office to wait for whatever was going to happen next, numb. The Boss stuck her head in minutes later to tell me that, since I was wearing a uniform, there was a plan for these sorts of things and we were going to execute it.

That was about the time my pal Eileen was sitting in her car on Rt 27 waiting to get through the jam to Memorial Bridge and get to her job in the attic of the Capitol when American Flight 77 flashed downslope from the direction of the Navy Annex on the hill, over her car then the heliport and into the Pentagon.

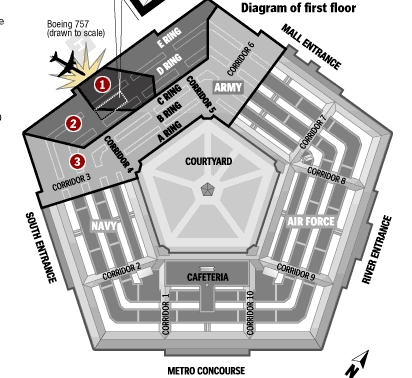

My pal John was blown out of his office in 3C265, across the corridor and at the bend of the building from the point of impact near the heliport.

When the images came on the CNN the camera angle made it plain that the aircraft had gone into the area where my old office had been moved in the big re-construction project. Flames rose from the sandstone below the roof. I tried to call my old number but all circuits were busy.

We were moving at that point, to a secure location on the campus, and I found myself with the Director and at a desk with a phone and nothing else.

“Get me the Director of NSA,” said George, and turned back to watch the CNN coverage as the unimaginable happened. His face went gray, gray as the plume of dust that was billowing from the disintegrating tower.

I had no phone book. I do not know how I got through to Fort Meade, but I did. “There is another airplane out there,” someone said. “They say it is coming here.”

I later heard everyone in town thought the same thing, from the White House to the Department of Agriculture.

You know the rest of it, and by then I was just another person watching television like you. Once the realization came that everything was grounded, except Air Force One, they realized that phones without phone lists were no good, they let us go back to our offices.

The Real Plan was going into effect, the one no one talked about, and the Grownups were disappearing. I shuffled paper at my desk until sometime after a lunch that did not happen. I dialed cell numbers randomly to see if any of my co-workers at the Pentagon had survived. I finally got a call through to my old staff.

A pal said she had seen the fireball out the window, but the office was intact, and everyone had got out safely. I was bathed with relief and the sour scent of adrenaline.

The Boss was maybe mobilizing with The Plan. She did not need the three or four us still in the vault. “There will be plenty to do tomorrow. Rest up, if you can. Go home.” she said. I did not have one, and I did not know if it would be possible to get back across the river to Fort McNair. I felt lost and more alone than I ever have.

As it turned out, the drive to the District, past the largest crime scene south of Manhattan, was a piece of cake. There was no traffic on the Parkway, and I saw people roller-blading on the bike path. It was a beautiful day.

I had a big bottle of Popov Industrial Strength Vodka back in the room, and I was able to knock back enough of it out on the stately veranda, watching the soldiers swarm around on post, and as darkness came on, the bright orange of the Pentagon burning across the Potomac.

In my relief that my old office had survived, I discovered that the Navy Command Center had been at ground zero, and Vince and Dan and the other kids from ONI who worked the intel watch were still in the building.

Damn.

The Boss was right. There was plenty of work to be done, and it is not done yet. There is a ceremony at Arlington this morning, but I normally stop by later in the day, when the people have departed and I can pay my respects privately to those who rest so close to where they were martyred.

Copyright 2014 Vic Socotra

www.vicsocotra.com

Twitter: @jayare303