Tradecraft

(1966-vintage shrapnel from a rocket attack in Saigon).

Willow was quiet, but it was a wary quiet, awaiting the arrival of people who would drink away the stress of the day. Old Jim was listening to music on his MP3 Player, Mac Showers was dressed casually in an aloha shirt and slacks. Jasper was holding down the bar, waiting on Big Jim to arrive to handle the Happy Hour crew. Heather 2 was on the wait-staff, though they had been auditioning her to work the bar as a fill-in, due to the loss of Brianasaurus Rex, who had left Willow for what we understood were “creative differences” with management about the cut of her tight Lycra top stretched over her imposing décolletage.

There is always a moment of silence when one of the bartenders departs the family, and Briana had been warmly welcomed, at least at our end of the Willow bar.

(RADM Donald “Mac” Showers in his customary aloha shirt).

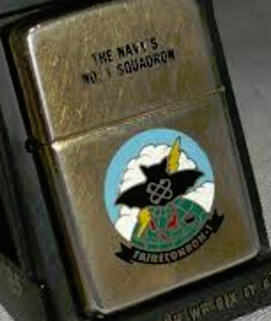

I was in my grown-up work clothes with a jaunty bow tie. The Admiral fished in the front pocket of his slacks and brought out two objects. One was one I recognized immediately- it was a battered Zippo lighter with the squadron logo of Fleet Aerial Reconnaissance Squadron ONE, the West Coast intelligence collection aviation unit. The other was something I did not recognize- a nasty looking twisted piece of metal that despite its tarnished exterior radiated a passive hostility.

“OK, I’ll bite. I recognize the lighter and have dozens of them. I used to collect them, in fact. But what it the other thing?”

“Well, you can add the Zippo to your collection, and we are going to talk about VQ-1 one of these afternoons. The other thing I thought you might find interesting. I found it the other days going through an old box. It is a piece of shrapnel from a VC rocket that was used to attack the Meyercord Bachelor Officer’s Quarters one night in Saigon while I was there. I walked through the wreckage the next morning and picked it up as a souvenir.”

I picked it up from the bar. It was as ugly a thing as I have seen. The edges were still razor sharp where the high explosives that the steel shell casing had enclosed had turned it white hot, twisting and ripping as the missile tore into the cinder-block façade of the BOQ.

“That would get your attention right quick,” I sad, putting it down before I nicked my finger on the sharp edges.

“You bet. Particularly traveling at more than a thousand feet a second. No one got killed in that attack. Not any of our guys, anyway. But that was the Saigon experience.”

“I only visited that town once, Admiral. Much later, of course. But it was an amazing trip.”

“Oh,” he said, brightening a bit and leaving Saigon behind. Or ahead, if you were trying to follow the wandering Willow narrative. “After our talk last week, I was thinking about my tour at the Schoolhouse. I look back at it- the tour I didn’t want to do, and upon reflection, it was one of the best and most satisfying of my Navy career. After talking about it with you last week, I thought of some other memories of that time. I was almost discouraged about having had my orders changed and having been sent to an environment with which I was totally unfamiliar. I hadn’t asked for it, hadn’t thought about it, and didn’t really care much about it.

“What was the course work like? What did you try to teach the new Ensigns if you couldn’t use classified information to teach them?” I decided I really liked this version of the Happy Hour white. Curiously refreshing, and I almost lost track of educational challenges in the Intelligence Community. Mac was able to drag me back.

“Well, that was one of the challenges. “In the course of the two years that I was there, I instructed four classes, four complete classes, start finish. These classes averaged 80 or so officers per class. In my two years, I was privileged to work with and instruct perhaps 300 or more officers. Probably half or two thirds of those officers were Ensigns who had been commissioned in the Officer Candidate School at Newport and were now coming through Intelligence School. The balance of the class was composed of unrestricted line officers who were taking on intelligence as a subspecialty, and they ranged in rank from Lieutenant to Commander. Each faculty member was assigned a proportional number of students for whom he was ‘faculty advisor.’ So, in addition to working with the class as a whole, each instructor worked intimately with perhaps fifteen or so individual students for whom he was faculty advisor.”

“I remember the courses at Denver started out with ship recognition and some basic photo interpretation. It was fairly basic stuff until our clearances came through and the instructors could talk more freely about what we were really going to be doing.”

Mac nodded. “In my time the basic course started out with Professor Francis “Frank” Decelles. He was, incidentally with the Naval Postgraduate School system, which had jurisdiction over us, He was the senior professor in the Naval Postgraduate Schoo1 system. He was one of our links to Monterey. During our six-month course, would hold forth for the first six weeks full-time. All lectures. Essentially, he really lectured for about four hours in the morning. In the afternoon, then, we would have discussions, seminars, and various other activities to give some variety. But the first six weeks were devoted to Professor Decelles lecturing on world politics and the political scene, history, geography, whatever.”

“It is a wide world out there and a lot of folks don’t pay much attention until they actually have to visit it.”

“I never did take the Decelles course, so I can’t tell you exactly what he covered. I used to sit in on some of his lectures. He was a good lecturer; a flamboyant man who loved to talk. He did this over and over, course after course. When the curriculum was expanded from six months to twelve, Frank’s courses simply expanded to eight weeks instead of six, so he could talk more.”

“I have shared the misery of having to listen to military people who thought they had a lot to say, and plenty of PowerPoint slides to back it up,” I said, wincing at the memory.

“It can be painful. Then, after Decelles’ course was finished , we started our instruction in various aspects of naval intelligence techniques and tradecraft and so forth. Field training was essential. As I mentioned last time, we’d go to Quantico, or Patuxent River, or David Taylor Model Basin, and we’d put them in the role of an attaché — a foreign attaché– observing a U.S. base or activity as an exercise in tradecraft. They would even take pictures, like the Moscow attaches would on Schmidt’s Embankment in Leningrad, the only place we could get a look inside the doors of the covered building halls where the new generations of Soviet submarines were being constructed. Satellites could not see through the roof, after all. Sometimes low-tech is the only way to collect effectively. After we returned from the trip, the students had to write a report. They would try certain little techniques of discreet activities not to get “caught” collecting. Some worked well and some didn’t. I think that’s something that an individual designs himself and picks up rather than gets taught.”

“I completely agree. When was your tour up at the school?” I asked, underlining the word “tradecraft” on the napkin in front of me.

“January, 1957, two years almost on the nose. We had just graduated a six-month course before Christmas. I am glad we talked about it. In thinking back, and I still look back on it to this day, it was one of the most rewarding tours that I ever had in Naval Intelligence. I think it was mainly because I was working with a large number of people, and getting acquainted with them. Wherever I went and whatever I did for years afterward, I would encounter these people in various pursuits, assignments, and walks of life. They didn’t all stay in the Navy, obviously. They would remind me that I was one of their instructors in Naval Intelligence School, and frequently they would remember, and I wouldn’t — mainly because there were so many students and I didn’t get that close to all of them. “

“I had the same thing happen after I was the junior Assignments Officer. I always wondered if one of my former clients find me in an alley or a dark parking lot and try to beat the crap out of me.”

“Apparently I did a better job at the Schoolhouse,” he said with that twinkle in his eye. “It happened to me all over the world for many years, and it still is rewarding that we were able to make an impact on so many lives. An example of that is Senator Dick Lugar. He went to OCS and came to us as an Ensign; he did his time in the Navy and then went back to Indiana politics, became mayor of Indianapolis, and whatever, House of Representatives, and then a United States Senator. Many years later when I was with the Director of Central Intelligence, I was testifying before the Senate Intelligence Committee, and Senator Lugar came up to me and reminded me I had been one of his instructors at the Naval Intelligence School. He was not one of the students for whom I was faculty advisor, and frankly I didn’t remember him being there. But that’s one of the gratifying things that grew out of those orders to Anacostia. And we might have taught those officers how to read and write, which certainly worked out for Dick.”

(A young Senator Richard Lugar, R-IN).

“As a general proposition, I believe in literacy for our public servants, Admiral.” I took a deep pull off my Happy Hour White, put it back down on the bar and tried to remember what I had thought we were going to talk about. “But weren’t we going to talk about your time at FIRST Fleet out in San Diego? That was my favorite place to live in all the United States.”

“In those days I would have tapped a cigarette out of the pack and flipped open my Zippo to light it.”

“I remember those days,” I said, having had a Marlboro on the walk over from the office. “I guess the world has moved on a bit, wouldn’t you say? Now, about FIRST Fleet….”

Copyright 2017 Vic Socotra

www.vicsocotra.com