Water Water Everywhere

(A colorized shot of IJN Nagato in her better days with a real crew and a war that was yet to be lost. Photo National Archives).

Editor’s note: Early in my naval career I had the rare opportunity to serve in a World War Two warship. Commissioned in 1945 as a “CVB,” (aircraft carrier- armored) USS Midway (CV-41) was built tough and built to survive anything the Japanese could hurl against her. She had steamed hundreds of thousands of miles and served in two wars by the time I met her, and suffered the indignity of dozens of ship-alts that would have made her unrecognizable to her original builders. Moreover, since she had been ordered to Yokosuka to serve as the centerpiece of the Overseas Family Residence Program (OFRP) all her yard work was performed by Japanese craftsmen, and her inner workings were best known to the little men in their breeches and tabi shoes.

One interesting feature of life aboard was the peculiar taste of the water, which varied seemingly by time of day. All the pipes and tanks were cross-connected against the eventuality that some might have to be flooded to keep the mighty ship upright, even if the hull’s integrity had been breached. That meant that there were valves that connected fuel and water, and in a ship that was already more than thirty years old, some had been opened when they should not. The most graphic demonstration of that was the ability to light off a pale flickering blue flame on the top of a cup of Mission Planning coffee. I have no idea of the long-term implications of drinking a modest amount of kerosene (JP-5) each day, but we learned not to worry about it overmuch. For the rag-tag pirates of the ex-IJN Nagato, the matter was much more personal, and even the location of the pipes was an unknown factor. Join Ed Gillfillen this morning as he describes the men and the situation aboard the battleship.

-Vic

(The reality of Nagato in 1946. “Rode hard, put away wet” would be the best way to describe her last days. Photo National Archives).

The officers who were rounded up to command the last Japanese battleship soon found that the men in their charge could not be driven. The war was over, after all, and all the imperatives to duty had been minimized. There was no enemy, except the mighty sea herself. I found I could call for a working party to muster and get it; but the minute my look was turned, the men would melt away into the caverns of the ship, where no one could find them.

Another officer would explain how he wanted a thing done and go to the wardroom for a cup of coffee, but nothing would come of it; he could inquire why and be told that the necessary materials could not be found. Being sure that the men know full well where the materials were was no help – he didn’t. Any attempt to stand by and instruct the men step by step was frustrated by passive resistance; they would stand, helpless, asking, “What do I do now, Sir?” as though they had never seen anything done like that before. In time, even the dumbest officers realized that the men could not be driven, and only one or two of them found that they could be led.

The situation with respect to water and oil tanks was a nightmare. Most of the valves controlling the fluids were inaccessible and one could never be sure they were completely closed. There was no reliable way to find out what or how much was in the tank. Oil circulated through the ship continuously; it might be anywhere. From the same tank one night got oil one day, nothing the next, the salt water and perhaps after a week oil again. We kept watch over the side and know that all the oil we took stayed with us until it went up the stack. We did not know how much was in the ship to start with, nor could we be sure how much of the tanker pumped in was actually salt water. Some of the most conventional-minded officers had difficulty adjusting to the situation.

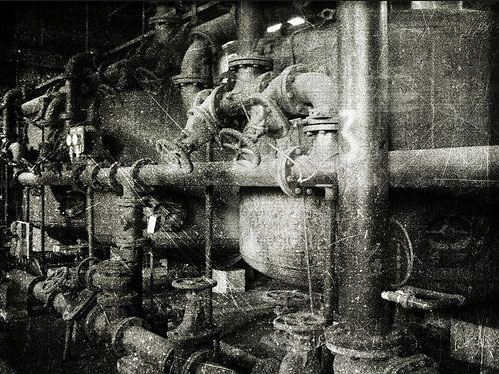

(What is connected to what? The only certainty was that it all was, somehow).

The idea of shortages of fresh water brings sailing vessels and oak casks to mind, but we had the same problem with a modern twist in the Nagato. We were distilling five or six tons an hour from seawater. Much of that went into the boilers. Theoretically, they use the same water over and over again, but some was lost each pass through the mass of not-so-tight steam pipes. What did come back was always contaminated with seawater. This would make the boilers sick and they would vomit to the sky as the steam roiled and have to be purged into the bilges.

We would have liked to use water drained from the boilers in the laundry, but never found a practical way to get it there. What would be spared from the boilers was pumped into the fresh water arteries of the ship and some of it actually got to faucets, but most of it mixed with saltwater seepage in remote compartments. We were always looking for those leaks, forming the habit of tasting anything that dripped, and we finally stopped many of the leaks, but our fresh water accounts never came anywhere near balancing, and in the end, it was not as much about balancing the accounts, but keeping the mighty ship herself balanced and upright.

That actually became on of the real problems.

Copyright 2015 Vic Socotra

www.vicsocotra.com

Twitter: @jayare303