Welcome Aboard, Ensign Showers

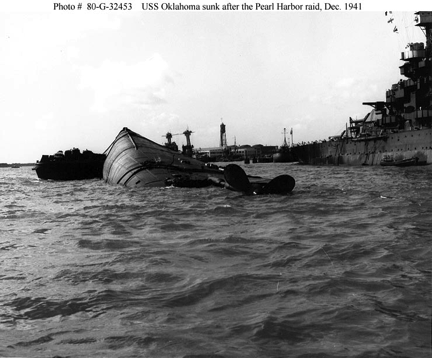

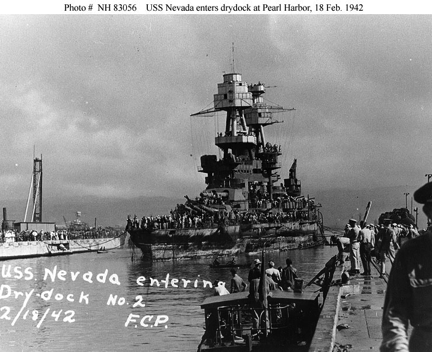

Editor’s Note: It being just a whisker away from the day we are supposed to never forget, it seems appropriate to delve into the Wartime interviews with Admiral Mac Showers. Mac had arrived in February of 1942, fresh out of his Counterintelligence and Public Affairs training in the Pacific Northwest. By pure dumb luck he avoided being captured and imprisoned by the Japanese with half of his graduating class, who had been dispatched to Manila and were immediately interned by the invaders. Mac had attempted to report to the assignment for which he had been intended- working downtown and looking for signs of espionage. Disparaged by the Detachment OIC, he was deemed unsuitable for CI work due to his inexperience, and was instead sent to fill a requirement for a body at the Naval Shipyard at Pearl Harbor. The big ships were still on the bottom from the attack on December 7th. Oklahoma was still capized, and Nevada was just entering dry-dock for her restoration. As we approach the 75th Anniversary of the sneak attack that changed a world, think about what it must have been like for a young officer reporting to the war. Shipyard workers labored around the clock to make the ships whole once more, and the gentle traadewinds ruffled the fonrds of the palms around the 14th Naval District Headquarters beneath which lay The Dungeon, and the codebreakers of Station HYPO.

Remember Pearl Harbor.

– Vic

(USS Oklahoma (BB-37) capsized at her berth on Battleship Row in Pear Harbor. Years later, walking along the shore, fragments of the steel cables used to bring her upright once more were still strewn on the sand. Official US Navy Photo.)

I looked with dismay at the plastic bag from Bed Bath and Beyond that Mac placed on the tall cocktail table. There was a book about the Berlin Airlift I don’t have time to read, and the CIA monograph that I will make time for. I waved at Peter to get a glass of the loss-leader Happy Hour Pino Grigio.

“The CIA publication only has about fifty pages of text,” said Mac. “But the exhibits in the back are reproductions of the original documents- minutes of meetings and policy memos- they are fascinating. It shows how Truman made his decisions to use The Bomb against the Japanese. Our estimates played a key role in that process, even if we are not mentioned by name.”

“Yeah,” I said, smiling as Peter filled the bubble-shaped wine glass to precisely one-third of its depth. “But we talked about the end of the war last week and missed the beginning. I want to hear about 1942, when you first got to Pearl. I want to know what you did, what the job was like, what your battle rhythm was.”

Mac nodded and took a sip of his Virgin Mary. “Did you know that at one point I had four military identification cards with four different colors of eyes?” He took off his glasses and leaned forward. His blue eyes sparkled with amusement. “Blue, Gray, Brown and Hazel. What do you think?”

“I would say blue,” I said, wondering if the pork spring rolls were still on the Willow Bar’s ‘neighborhood bistro’ menu. They are tasty little rascals. “Though I suppose they could be hazel or gray. I have never understood the color hazel.”

Sara-with-no-H wandered by and asked if we were hungry, and we were. We ordered a couple of the tapa-sized snacks. “So we have done the big stuff, the pivot points of history and all that. What was life like? What did you really do?”

Mac contemplated the question, since he was usually asked about the matters of primary interest for those of use who came after, the sinking of mighty aircraft carriers and the mushroom clouds. “Well, after I was abruptly dismissed by that cowboy Officer in Charge of the Honolulu detachment of the Navy Investigation Service, I was sent out to the Shipyard at Pearl. The Cowboy figured he could use me to fill a lingering requirement levied by the staff of Admiral Nimitz.

It was February, 1942, you know. The big boats are still on the bottom of the harbor. USS Oklahoma still presented her keel and one massive brass propeller pointing to the puffy clouds. Nevada was just being re-floated, and came back into the harbor for dry-docking in the middle of the month. I arrived at the Admin Building at the shipyard, presented my orders in triplicate at the quarterdeck, and was eventually shown down to the basement and presented to Commander Joe Rochefort, the OIC.”

(USS Nevada (BB-36) entering dry dock, 18 Feb 1942 near the 14th Naval District HQ and CIU/Station HYPO where Mac was just reporting. Official Navy Photo.)

My ears perked up. “So you went to work for him?” I made a note on the napkin in front of me, nearly knocking over the wineglass, which was wedged against the plates and cloth napkins and silverware we don’t use to eat the snacks. “At the Fleet Radio Unit- Pacific?”

“No,” said Mac with mild irritation, as though he was talking to a slow-learner. “We were known as the Combat Intelligence Unit, the CIU. No, Joe Rochefort just said “Welcome Aboard, Ensign. He knew that I didn’t have any Japanese language training or expertise with the IBM ECM Mark III punch-card tabulating machines. CDR Rochefort gave me over to Jasper Holmes, and I started to make files.”

“Files?”

“Yes. Ditto files. Do you know what that is?”

“Like mimeograph machines? I remember those from grade school. And the smell.” I wrinkled my nose with the memory.

“Our fingers were purple at the end of the day from the fluid. I will get to how we eventually got inside the Japanese code system, but I need to explain how this all worked.”

I nodded. “That would be useful,” I said and winced as I bit into a spring roll that was still blazing from the hot oil of the wok in the kitchen. Damn, those things are tastey.

“The Japs had introduced what we called the JN–25 code system in mid-1939. It consisted of about 33,000 words, phrases, and letters and was the primary code they used to send military, as opposed to diplomatic, messages. After Pearl Harbor, the CIU focused on cracking that code, though we also had success with a lower-grade code the used for controlling their merchant ships. That is what we gave to the submarine force.”

“When did the CIU get into the code?” I asked, swirling a little of the dry white wine in my mouth to assuage the burn. I noticed there were some very attractive women at the bar, concentrating exclusively on one another and I wondered if Willow was attracting the lipstick lesbian crowd. If it was, I was all in favor of it.

“CIU had some success starting the month before I got there, in January. But it was hard. That is why the files were so important. But let me explain the way it worked. OP-20-G was the staff number assigned to the Code and Signal Section of the OpNav staff at Main Navy back in Washington. We were station HYPO, named for the first letter in Hawaii. Station CAST was on Corregidor Island in the Philippines, and so on. NEGAT was at the former girl’s school on Nebraska Avenue in Washington. There were over seven hundred people assigned to the effort.”

“Was it NEGAT that got the “East Wind Rain” message that signaled the attack?”

Mac snorted. “There never was an East Wind message. That is all nonsense. Commander Safford was the only one who testified that he got it, and that was after the war in the testimony to Congress about who was responsible for the Pearl Harbor attack.”

“OK, I know the target code, and the big issues. I am interested in what it was like to work at HYPO and what you did, how you got around, what the hours were like. You know, what it was like to be at war with the Japanese looking invincible.”

“Well, to do that I will have to tell you about how I made a Frankenstein sedan, and a little about Jasper Holmes, who had quite a career writing for the Saturday Evening Post.”

I knew it was time to get a fresh napkin, and waved past the pretty ladies to Peter to see if I could get some more wine.

Copyright 2010 Vic Socotra

www.vicsocotra.com